Native to the Amazon, cacao helps preserve the forest intact, generate income and recuperate degraded areas. With demand outpacing production, the chain connected to the fruit in the country still lacks incentive for growth and development for local producers.

In the shadows of the largest rainforest on the planet, cacao trees grow out of sight. The Theobroma cacao tree can grow up to 20 meters tall and is known for its fruit, which produces one of the most appreciated foods in the world: chocolate. It’s been in the Amazon for at least 7,000 years. Long before anyone thought.

For a long time, it was believed that cacao first appeared in Central America around 3,000 years ago. In 2013, a study by researchers from Ecuador and France revealed archaeological traces of plant cultivation and management in the province of Zamora Chinchipe, in the Ecuadorian portion of the Amazon. The research showed that the domestication of cacao and its consumption had taken place in Ecuador at least 1,500 years before previously believed. It extended through the Peruvian forest to the upper regions of the Amazon River and later reached such countries as Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala and Nicaragua and then North America.

No one can say for certain how and when cacao arrived in the Brazilian Amazon. Its cultivation, however, probably began in the late 17th century with Portuguese colonization, first introduced in Pará, but with production consecrated in another biome, the Atlantic Forest, more precisely in the state of Bahia, especially from the 19th century on. The golden age of cacao, in the first half of the 20th century, earned a lot of money for large-scale farmers in the vicinity of Ilhéus, in the south of the state, and made Brazil the second biggest producer in the world. It is estimated that cocoa bean exports reached 370,000 tons per year, the equivalent of 25% of the world’s total production.

Only in the late 1980s, when the crop was heavily affected by a fungus, did national production begin to lose steam. Known as “Witch’s Broom,” the mold spread rapidly and devastated entire crops, cutting production by more than half and plunging thousands of people into poverty. Curiously, the same fungus had previously destroyed cacao crops in Ecuador decades earlier.

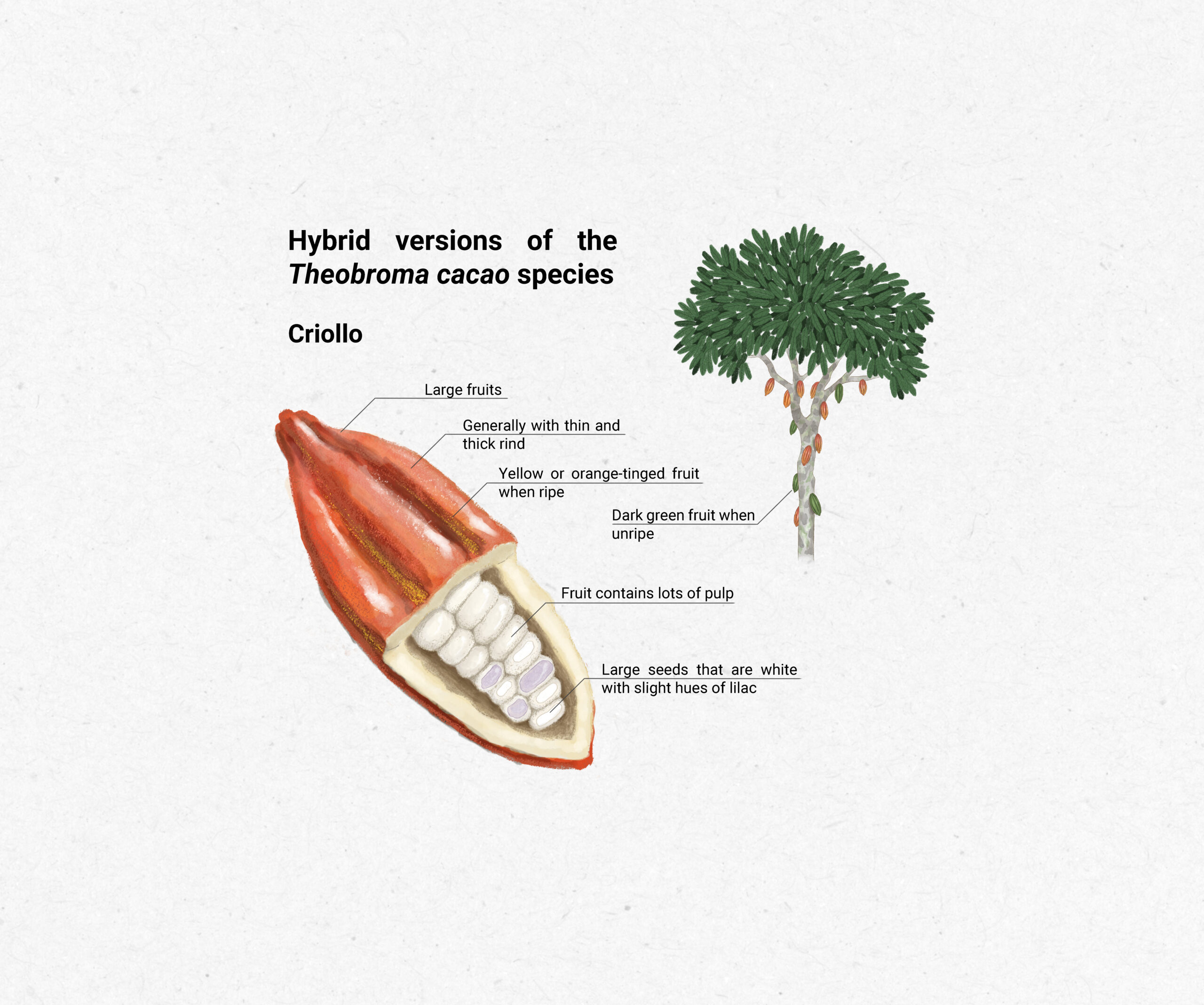

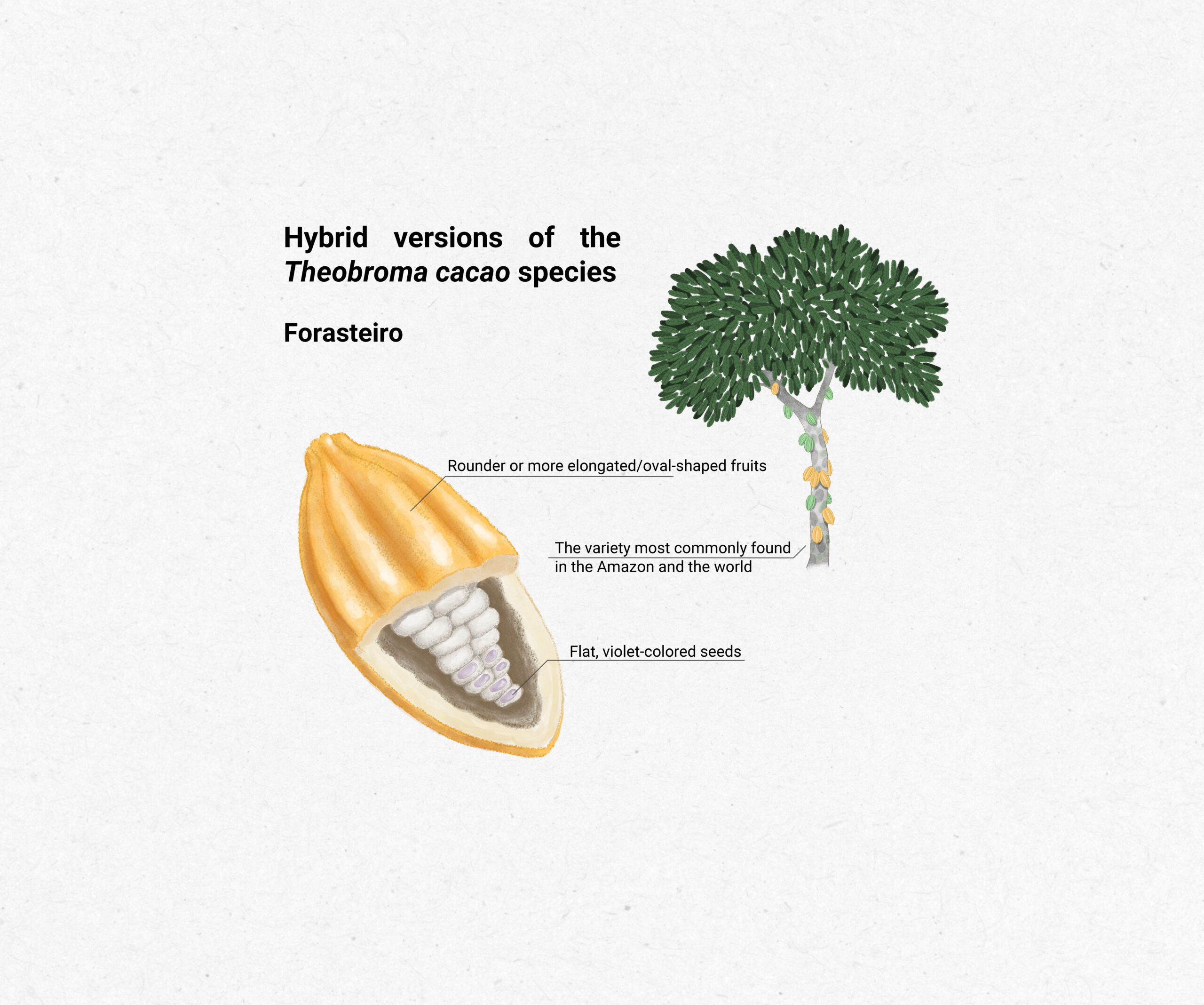

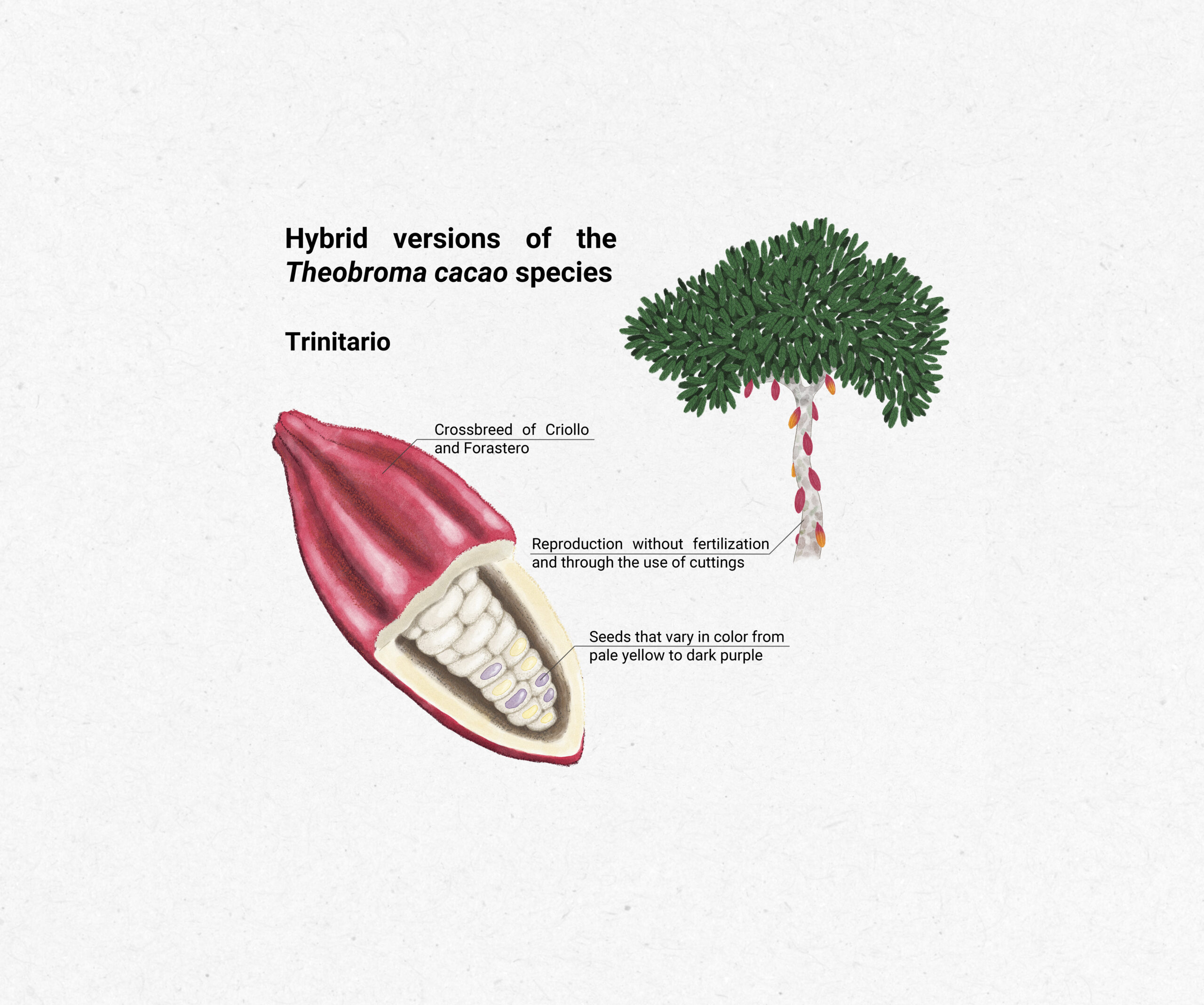

To deal with the problem, an agency linked to the Ministry of Agriculture, known as the Cacao Plantation Executive Planning Committee (Ceplac), was created to work for sustainable rural development in the cacao producing regions through technical assistance, training and programs to improve performance and economic efficiency. Among its strategies to revive production, the commission established guidelines for the use of mixed and/or cloned varieties of the plant that are more resistant. There are three predominant types: forasteiro, criollo and trinitario. After languishing for many years, the activity is once again showing signs of growth.

“Compared to other cacao-producing countries, Brazil has the entire chain, from production to consumption, established here. It is the fifth largest consumer in the world and we have an idle capacity in the industry. So, if we produce cacao, the industry absorbs it. There is no supply problem. On the contrary, today, there is a cacao shortage. The industry imports cacao from Africa to meet this need. I think that in the short/medium term, due to the investments that have been taking place in the chain, we will soon be self-sufficient and Pará has a lot to contribute to this,” explains Guilherme Salata, coordinator of Cocoa Action Brasil, a public-private initiative of the World Cocoa Foundation funded by eight food industries.

Brazil has the entire chain, from production to consumption, established here. It is the fifth largest consumer in the world and we have an idle capacity in the industry. So, if we produce cacao, the industry absorbs it. There is no supply problem. On the contrary, today, there is a cacao shortage. The industry imports cacao from Africa to meet this need.

Guilherme Salata, coordinator of Cocoa Action Brasil

Wild cacao from the Amazon

Rural producer João Dorismar da Paixão was born and raised in Amapá. At an early age, he accompanied his mother and aunts in the extractivist harvesting of wild cacao in an area known as Vila Velha, a stretch of 31 kilometers along the banks of the Cassiporé River. The lowland forest of the region is comprised of andiroba, pineapple and açaí trees.

He left to study in the municipality of Oiapoque. Decades later, he returned to his homeland, and as his last name suggests, discovered a passion for cacao. Two years ago, he set up a small factory and became a chocolate producer, adopting the name of the river, Cassiporé. The process is virtually artisanal. In the harvest period, he works with 12 families from local communities.

“They bring the whole fruit in the canoe to the base. There, they break them and, once they’re broken, they’re weighed and I pay for them. After, the rest of the work is up to me. I have an employee who does the whole fermentation process, obeying the Ceplac and Embrapa protocols, and which we adapt to our reality, because it’s not the same as planted cacao. Native cacao is different. Then comes the drying process in the winter. When the harvest is over, we bring the cacao, formerly seeds, now beans, to Oiapoque. There, we do the processing, the selection, the roasting and the breaking, to separate the bark from the nibs. We take it to process and make the delicious 50%, 70%, fine chocolates,” he describes.

According to Paixão, a study of viability indicated that Vila Velha’s production capacity is 42 tons per year. “We haven’t reached that level yet. In 2018, we produced 1,600 kilos. After that, we got up to 2,000 kilos. Then the pandemic came. Last year, it was 3,000 kilos and this year we have the prospect of harvesting 6,000 kilos of cacao.”

As someone who grew up seeing the importance of preserving the forest firsthand, Paixão advocates for a limit in production so that the place where he spent his childhood can produce fruit for a long time to come.

“We’re not going to dream beyond what is possible. Who knows how many thousands of tons… no way! It’s going to get to the point where it’s enough. Let’s be content with what we have and preserve it. We need to value those communities so that they can have opportunities for income and show that it’s possible to live off of extractivism, off of the products of the forest, without cutting any trees down.”

We’re not going to dream beyond what is possible. Who knows how many thousands of tons… no way! It’s going to get to the point where it’s enough. Let’s be content with what we have and preserve it. We need to value those communities so that they can have opportunities for income and show that it’s possible to live off of extractivism, off of the products of the forest, without cutting any trees down.

João Dorismar da Paixão, rural producer

The enthusiastic rural producer says he has worked to offer different products to his public and has his own store, which he intends to transform into a network all throughout Brazil. Paixão’s initiative caught the attention of Luiza Abram, a specialist in fine chocolates who holds a degree in gastronomy. She became known for her work with wild cacao provided by extractivist communities in the Amazon and today produces a line of chocolates in partnership with the rural producer from Amapá.

Pará: the biggest cacao producer in Brazil

Other initiatives like Paixão’s are popping up in the Amazon and Brazil is currently the seventh largest cacao producer in the world. Despite its relatively good position, the nation accounts for less than 5% of the planet’s total production. Almost all of it is absorbed by the domestic market and exports are still considered insignificant. In the past, Brazil was the second largest producer, accounting for 25% of the world’s total, thanks to the cacao that came from Bahia.

In the Amazon, production is basically concentrated in the state of Pará, which is responsible for over half of all of Brazil’s cacau and 96% of Northern Brazil’s output. In 2022, 132.124 thousand tons of beans were produced, with more significant production in the municipalities of the Transamazonian region. These numbers are taken from the report “Safra de cacau no estado do Pará – 2022/Ceplac” [“Cacao harvest in the state of Pará – 2022/Ceplac”] sent to InfoAmazonia. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), Brazil produced 270,000 tons of cocoa beans in 2020/2021. The states of Rondônia, Amazonas and Amapá, respectively, round out the production.

Adriano Venturieri, an agronomist and researcher from the Brazilian Agricultural Research Company (Embrapa), uses satellite images to survey land use in the Amazon in partnership with the National Research Institute (INPE) for Projeto TerraClass. Before, in a more general manner, with areas classified as pasture or secondary vegetation, utilizing a system that did not differentiate between areas of perennial agriculture such as cacao, palm or coffee. Later, with more advanced technology, it was possible to recognize the crops. Venturieri then implemented a plan to monitor the cacao in the state of Pará, the nation’s main producer, and cross-referenced data obtained from the Cadastro Ambiental Rural (“Rural Environmental Registry”), or CAR. To validate the information, he relied on fieldwork and participation from local communities.

In the first stage, which lasted until 2019, Venturieri identified 70,000 hectares of cacao. In the next two years, he got up to 90,000 hectares. From that point on, the agronomist and his team conducted analyses that demonstrated why cacao is considered an ally of the forest, contributing to the restoration of degraded areas. The results are published in the article, “A expansão sustentável do cacao (Theobroma cacao) no estado do Pará e sua contribuição para a recuperação de áreas degradadas e redução do fogo” [“The sustainable expansion of cacao (Theobroma cacao) in the state of Pará and its contribution to the recuperation of degraded areas and fire reduction”].

It was observed that cacao is predominantly planted on small, family farms inside agroforestry systems, where crops of various species are grown together, similar to what goes on in a forest. “We observed that there is less deforestation on properties that have cacao than those that do not. Another important thing we noticed: 75% of the area that we have surveyed so far, the 70,000 hectares where cacao is currently found, was deforested before 2008, prior to the date of the new forest code. The other 25%, most of it was on top of pasture,” Venturieri explains.

In addition, the researcher from Embrapa explains that cacao production also plays an important role in reducing the use of fire for agriculture: “The Amazon is filled with extremes. There are landowners who have technology at their disposal, but this is not the reality. Most people still employ fire as an agricultural practice. When you have a degraded pasture, you set a fire to clear the area. So, when you start planting cacao, the producer automatically stops using fire, because they aren’t going to set fire to a permanent plantation, which we call perennial. As such, wherever cacao went, there was a reduction in fires and consequently a reduction in the emission of greenhouse gases,” he says.

On the other hand, in the next stage of the surveying, Venturieri intends to step up the mapping methods in partnership with NASA and differentiate Sistemas Agroflorestais Agroforestry Systems (SAFs) from the plantations categorized as “full sun” – a type of monoculture practice – that have started appearing in Pará. With promises of increased productivity, this model worries scientists who fear a stimulus to deforestation.

“I see an expansion of risks for the region, in several ways, but the main one is the risk of cacao – like the moratorium on beef, soybeans – being accused of causing deforestation some time from now. If one property is accused of deforestation, it’s going to take the entire chain with it. It doesn’t matter if it’s my property or yours. So, this can have very serious consequences for the sector. There needs to be an agricultural policy to further value this cacao that recuperates areas, which is produced within an SAF and which does not present any differentiation, for example, in price for producers,” he warns.

The economics of the standing forest

Sustainable alternatives for income generation and inclusion of the local populations start with maintaining the forest intact, based on products and services from the forest that do not compromise the conservation of ecosystems, the so-called bioeconomy. While, on the one hand, the forest’s abundance might appear to ensure the future of its inhabitants, on the other, the absence of planning, investment and support for sustainable production chains from the authorities could put everything in jeopardy.

“We face challenges that are social, economic and environmental in nature, as well as the challenge to create an enabling environment. Cacao is a chain that has lost prominence and ended up without the same access to strong institutions and cooperativism that others, like coffee, sugar and corn, have,” explains Guilherme Salata, coordinator of CocoaAction.

According to Salata, almost all the cacao produced in Brazil ends up in the hands of the processing industries. There are essentially three multinationals that control 95% of the production. Although most of it comes from Northern Brazil, the state of Pará has just one small processor: Practically all the state’s production is sold to Bahia, where the by-products that become chocolate are made. Promoting the autonomy of the Amazon’s regional production chain and the workers involved should be one of premises of the bioeconomy.

“Our average productivity is still low, which puts farmers in a bad situation. Cacao productivity still isn’t economically viable, which ends up leading to other problems, such as (labor) informality. So, we keep coming back to this point that we need to improve productivity so that these farmers can rise up out of poverty. This is the way to meet other challenges. There are studies that show that from an economic point of view, though the bioeconomy, farmers do in fact manage to make a decent living off of cacao. We are talking about cacao that is 5, 6 times more profitable than livestock,” says Salata.

According to Adriano Venturieri, it is necessary to go beyond the monoculture of cacao: “Farmers need to sell and they don’t have a storage system, a system of cooperativism, and they have debts. Now, if they had another profitable perennial crop, along with the cacao, they would be able to keep up. They need to have alternatives to cacao. They’re not going to substitute it. They need to have it together and the SAF makes this possible. Açaí, bacuri…if the price of cacao isn’t good at a certain time, they can hold onto it and sell something else. But in order for this to happen, there needs to be an entire ecosystem of production. This is the big alternative for the small farmer, this integrated production. It’s the Amazon’s vocation, this forest production, the bioeconomy that is so talked about, but there needs to be an entire technology, a set of policies and territorial planning.”

Report by InfoAmazonia for the project PlenaMata.