An exclusive survey from the project Mentira Tem Preço (Lies Have a Price) reveals how Bolsonaro-supporting influencers and the President used digital platforms to tie terrorism and violence to MST (Landless Workers Movement) if PT (Workers’ Party) returned to the presidency.

In his first speech after the election results were announced, President Jair Bolsonaro (PL), who lost with 49% of the votes, said about the coup-supporting protesters that blocked highways across the country: “Our methods cannot be like those of the left, that always hurt the population, like invasion and destruction of property, and the curtailment of the freedom of movement.”

During the entire electoral campaign, the invasion of property served as a tool for Bolsonaro-supporting politicians and influencers to make MST (Landless Workers Movement) one of their main targets. Bolsonaro himself, in a press conference on July 18th, 2022, labeled the movement as “a terrorist group that was very active in Brazil not long ago.”

Far-right wing influencers used YouTube as a platform to reproduce this argument. Columnist Paulo Polzonoff, from the Gazeta do Povo channel, with more than 800,000 subscribers, referred to MST as “PT (Workers’ Party) heritage” in a video on September 23rd, which had 267,000 views.

The heat of the argument rose especially after the declaration by João Pedro Stédile, leader of the movement, who said that “Lula’s imminent victory will, as a natural and psychosocial consequence to the masses, be a rekindling that will motivate us to return to large mobilizations of the masses.” Pastor Sandro Rocha, who has more than 264,000 subscribers to his channel, said, without presenting evidence: “Do you think that MST should return to taking action in this country? Invading farms? Taking land from farmers, killing cattle, stealing tractors, which is what MST has always done?” The video has had over 102,000 views.

To justify the movement’s alleged violence, influencers used examples such as the invasion of the farm that belongs to former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s family (which really took place) and the destruction of a vaccine lab (which didn’t occur—what was actually destroyed was a research lab with genetically modified eucalyptus seedlings). In an interview for El País in 2018, Stédile said that both the invasion on private labs and the former president’s farm, in the past, should be considered mistakes committed by the movement.

How we did the study:

The project Mentira Tem Preço (Lies Have a Price), initiated in 2021 by InfoAmazonia and the production company FALA, monitors and investigates socio-environmental disinformation. During the 2022 elections, we checked the statements of all the gubernatorial candidates for states in the Legal Amazon region every day during the free televised campaign advertisement slots. We also monitor, through keywords related to social justice and the environment, disinformation about the Amazon on social networks, in public groups on messaging apps, and on platforms.

Mentira Tem Preço’s report questioned Incra (National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform) on the amount of rural estates invaded by MST. Such a number doesn’t exist. What can be affirmed is that the number of land invasions has been dropping in Brazil. According to Incra, the amount of farm estates invaded per year has been continuously decreasing: from 305 per year during Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s presidency (1995–2002) to 246 during Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s government (2003–2010), 162 under Dilma Rousseff (2011–2016), 27 under Michel Temer (2016–2018) and 40 during Bolsonaro’s term.

Even Bolsonaro entered the discussion. On his YouTube channel, he published a video on October 14th, directly attacking MST (using Lula’s phrases about the movement) and another group emphasizing, among other things, the “highest record of land titles granted” and “record numbers in agribusiness production.”

This disinformation has been disproved by Mentira Tem Preço (Lies Have a Price) in an article that shows that many of these land titles were temporary and that the agrarian reform, MST’s main demand, didn’t advance during Bolsonaro’s government.

Nonetheless, the statement was repeated by Bolsonaro-supporting channels on YouTube, like Foco do Brasil (where the video had 100,000 views); Folha Política (11,000 views); Francisco Mello, a channel that has 164,000 followers and also posted on the platform, but took the video down afterwards; and Kim Paim, with over 208,000 views. Kim Paim is one of the influencers mentioned in PT’s complaint to the Electoral Supreme Court for allegedly spreading disinformation during the 2022 election.

MST has changed, and for the better. There isn’t much space anymore for land invasion and big settlements.

ANTÔNIO MÁRCIO BUAINAIN, SPECIALIST IN AGRARIAN CONFLICTS AT THE CENTER FOR APPLIED ECONOMICS, AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT (NEA+) OF THE ECONOMY INSTITUTE AT UNICAMP

“MST has changed, and for the better. There isn’t much space anymore for land invasion and big settlements,” explains Antônio Márcio Buainain, professor at the Economy Institute at Unicamp (State University of Campinas) and specialist in agrarian conflicts at the Center for Applied Economics, Agriculture and Environment (NEA+) and of the National Institute of Science and Technology for Public Policies, Strategy and Development (INCT/PPED).

He has monitored land disputes in the country for decades and says he has always been a critic of MST, but that today he has a different view than that of years ago when he considered the movement “antidemocratic, disrespectful of the law, with practices that were unjustifiable in a democratic state.”

“They understood that, to strengthen the fight for agrarian reform, you have to show how viable the settlements are, how much they produce and contribute to the development of the country and for food security,” he says.

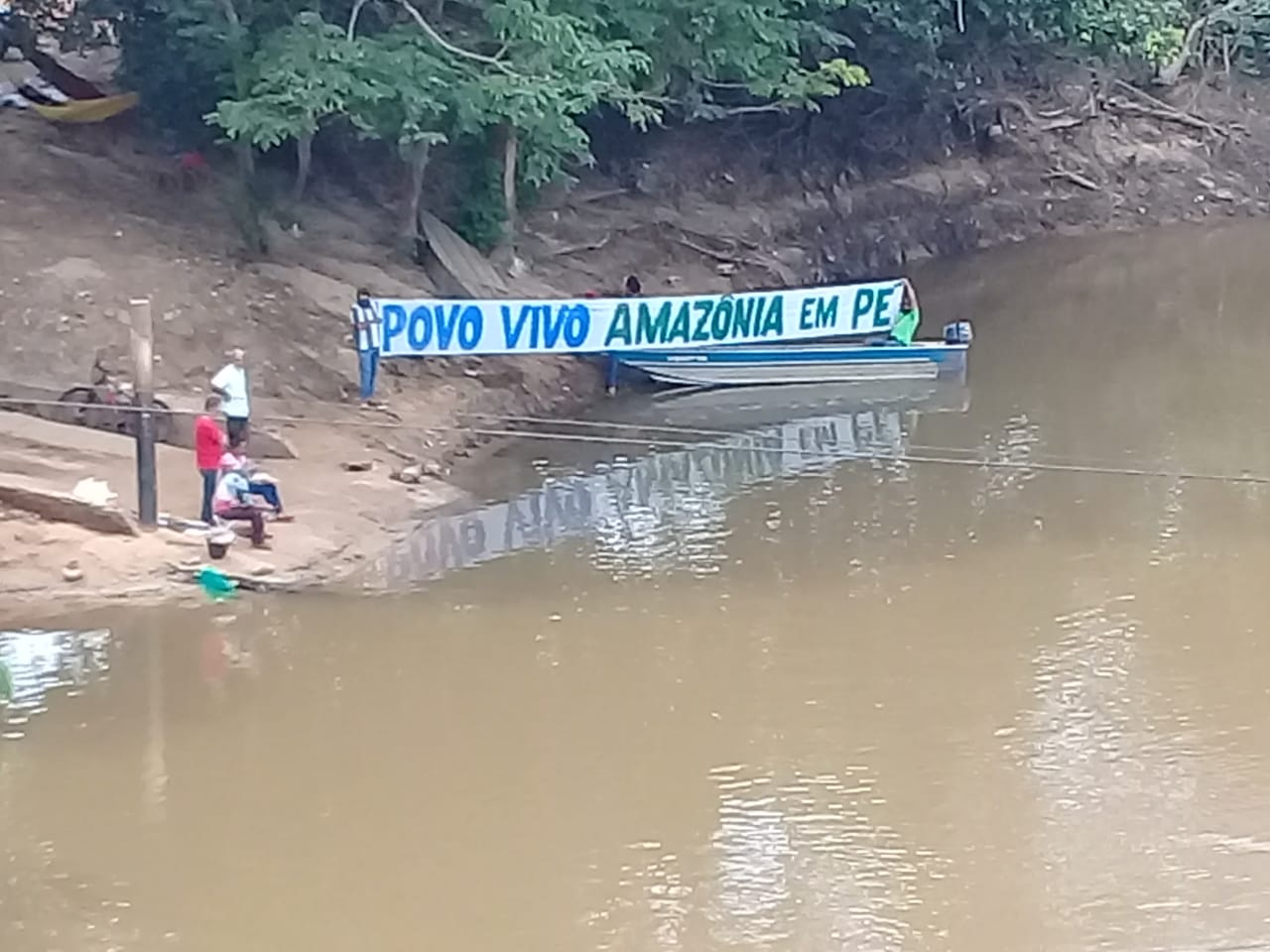

MST leaders say they don’t invade, but rather occupy land according to its social usage. An area that is not being used for the purpose it was created (such as a farm that stopped planting or that has irregularities in its work ethics) is not fulfilling the function of the property, and the movement considers it to be unused land.

“Not fulfilling its social function means that the land degrades the environment, makes use of slave labor and/or doesn’t produce. This land, having one of those elements, should, as our law demands, be expropriated for agrarian reform,” says Alexandre Conceição of the national coordination of MST, referring to the Constitution.

Banks and investment funds started buying land as a financial ballast, heightened by real estate speculation and increasing the cost of land in the field. The alternative was proposing another model of agriculture, based on agroecology.

PABLO NABARRETE BASTOS, AUTHOR OF THE BOOK “MST’S DIALECTIC MARCH”

The agrarian reform, however, became even more distant since the financial crisis of 2008. “Banks and investment funds started buying land as a financial ballast, heightened by real estate speculation and increasing the cost of land in the field. The alternative was proposing another model of agriculture, based on agroecology,” says Pablo Nabarrete Bastos, professor of the Federal Fluminense University Department of Social Communication, and author of “MST’s Dialectic March,” nominee for the 2022 Jabuti Award.

“Between the national congresses of 2007 and 2014, MST has undergone important strategic changes that culminate in their proposition for a popular agrarian reform. Undertaking an agrarian reform that is distributive, traditional or even liberal has never happened in Brazil, and it became too expensive to do it for fundamentally economic and political reasons,” he says.

According to Bastos, this popular agrarian reform means producing healthy and low cost food for rural and urban workers using a sustainable farming model, without pesticides, as opposed to agribusiness norms.

“It’s popular because it is of interest mainly to the workers. In a way, it seeks to sensitize and teach the city and the urban workers that the model works. That’s why the focus is on internal mobilization, the organization of production through co-ops and projects like the Armazém do Campo, that sells a diverse array of products coming from agrarian reform, from MST settlements, in strategic points of the cities,” explains the researcher.

In a way, this proximity between the countryside and the city creates a new line of action for MST, mitigating the need for invasion and large rural movements. According to MST estimates, there are 160 co-ops aligned to the movement producing food, corresponding to less than 30% of the production from co-op settlements and camps.

According to estimates by MST, in 2021, co-ops across Brazil sold R$ 400 million in products for school meals. The example of Armazém do Campo illustrates how settlers have increased production. The first physical store opened in 2016. Today, there are 20 stores and 40 commerce points across Brazil, and the prospect is that by 2025 they will grow to have 140 points of sale throughout the country.

This report is part of the project Mentira Tem Preço (Lies Have a Price)—election special, produced by InfoAmazonia in partnership with the production company Fala. The initiative is part of the Consortium of Civil Society Organizations, Fact checking Agencies and Independent Journalism for the Fight Against Socio-environmental Disinformation. They are also a part of the Initiative the Climate Observatory (Fakebook), the Eco, the Pública, Repórter Brasil and The Facts.

Content is authorized to be republished if published in its entirety. Mentira Tem Preço is not responsible for alterations to the content by third-parties.