During his electoral campaign, President Jair Bolsonaro (PL), a candidate for reelection, and his former ministers have highlighted the record number of land titles granted, but say nothing about those titles being provisional or how the government cut down Incra (National Institute for Colonization and Land Reform) funding dedicated to land reform and reduced rural credit by R$2.5 billion.

At the start of the second round of the Brazilian presidential elections, the distribution of land titles was highlighted amongst the campaign promises of President Jair Bolsonaro (PL), running for reelection. His October 7th TV campaign ad announced: “In the next term, President Bolsonaro will give land titles to all settlers in Brazil and will increase credit for those who want to grow and produce crops.” The subject also dominated discussions about environmental issues on WhatsApp and Telegram chat apps. Listed among alleged government achievements: “More than 400,000 rural land titles (land reform).”

In public groups monitored by the project Lies Have a Price (Mentira Tem Preço), videos and links boosted Bolsonaro’s campaign messages about the alleged feat by the President and his former ministers, like Tereza Cristina (Agriculture), now an elected senator for the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, and Tarcísio Freitas (Infrastructure), a Rio de Janeiro native who’s now a gubernatorial candidate for the state of São Paulo. But that land reform didn’t happen. In Brazil’s Legal Amazon region, the expedited delivery of land grants appeared in state government election campaigns, like in unelected candidate Teresa Surita’s (MDB-RR) campaign. Surita stated that she is “in favor of agro in all senses” and argued that granting land titles must happen fast.

The official discourse in favor of small farmers starts to crumble when analyzed more thoroughly, which hasn’t happened in land reform since Bolsonaro took office, say specialists interviewed for this article.

“This government is openly against the historical demands for land access and against the territorial rights of Indigenous peoples and traditional communities. This is different, because civilian governments, ever since the New Republic, have had to negotiate and dialogue with the social demands of the countryside,” says Sérgio Sauer, a University of Brasília professor, signaling the increased difficulty with which the traditional communities needs will be met in the event of Bolsonaro’s re-election.

This government is openly against the historical demands for land access and against the territorial rights of Indigenous peoples and traditional communities.

Sérgio Sauer, University of Brasília professor

In the first place, land title grants must be accompanied by a land reform policy that invests in settlement infrastructure, the demarcation of Indigenous lands, and the acknowledgement of quilombola territories.

How we did the study:

The project Mentira Tem Preço (Lies Have a Price), initiated in 2021 by InfoAmazonia and the production company FALA, monitors and investigates socio-environmental disinformation. During the 2022 elections, we check the statements of all the gubernatorial candidates for states in the Legal Amazon region every day during the free televised campaign advertisement slots. We also monitor, through keywords related to social justice and the environment, disinformation about the Amazon on social networks, in public groups on messaging apps, and on platforms.

According to Incra, the Bolsonaro administration granted 404,933 land titles between January 2019 and August 2022, versus the 332,818 delivered by Lula and Dilma’s governments. But Bolsonaro also reduced the budget for land reform to almost zero in 2021. A large part of those titles were issued by the current government in states in the North Region between 2019 and 2022, according to Incra. The states that granted the most titles were Pará (92,590), Rondônia (18,919), Amazonas (10,144), Acre (6,170), Amapá (3,429), and Roraima (2,543).

Also in 2021 there was a decrease of R$2.5 billion in the government rural credit subsidy. Pronaf (National Program to Strengthen Family Farming) lost R$1.35 billion. According to the administration’s original proposal, the program would be granted R$3.8 billion this year. Funding for family farming was cut by 35%.

The Bolsonaro administration also hasn’t demarcated the lands of Indigenous peoples or quilombolas in four years. “This government policy hasn’t brought any improvement to agrarian policies. On the contrary: it halted the creation of new settlements in Brazil,” said Andréia Silvério, who works with the national coordination of the CPT (Grazing Land Commission).

Why individual land titles are a risk

In areas that large mining and logging companies, farmers, and real estate speculators have set their sights on—such as large parts of settlement areas within the Brazilian Legal Amazon region—issuing individual land titles for people living in collective settlements not only opens up Amazon soil to the market, but it can also mean the destruction of existing social dynamics, says the specialist.

Granting individual titles within collective settlements allows these lands, kept inalienable by the collective stewardship, to become alienable.

Julianna Malerba, RESEARCHER AT NGO FASE

This policy leaves land unprotected from economic interests and dismantles the territorial and socially productive dynamics that are based on the common use of the land parcels by the families, according to Julianna Malerba, NGO FASE researcher and organizer of the series “Right to Land and Territory.” “Granting individual titles within collective settlements allows these lands, kept inalienable by the collective stewardship, to become alienable,” says Julianna.

This point was praised by former minister Tereza Cristina. “Families can now sell it, pass it on to their children and become more productive [with the granted lands],” she said as she celebrated during a land title granting ceremony in Mato Grosso do Sul, in March. This was just one of the occasions in which the senator elected by Mato Grosso do Sul complimented Incra’s work.

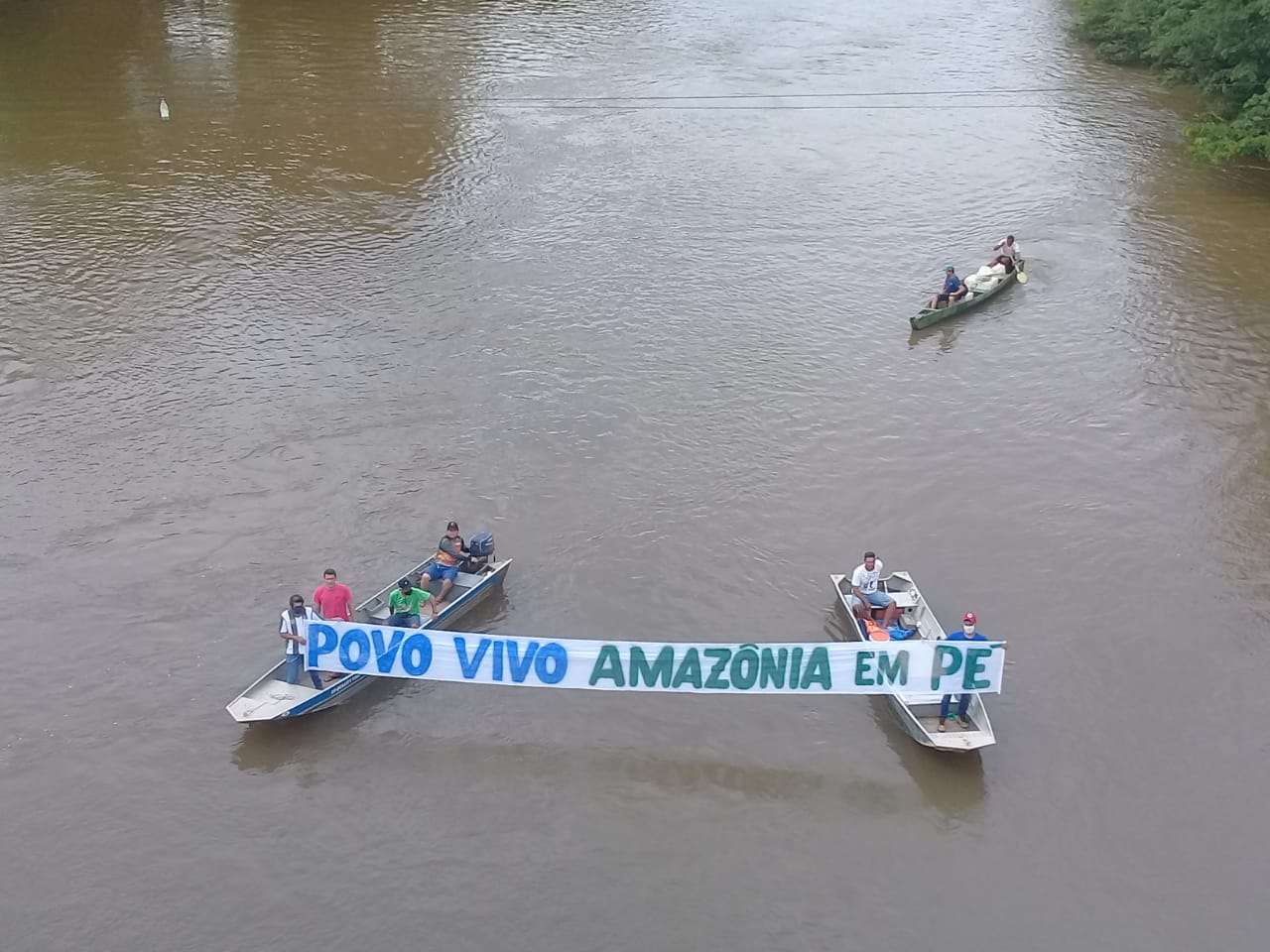

As an example of the issue of dealing with land titleship for individuals versus collectives, Malerba cites the Gleba Lago Grande Agro-extractivist Settlement Project (PAE), which she considers to be emblematic. Located in western Pará, between the Amazon and Arapiuns rivers, the region encompasses 154 communities and over 6,600 families in an area of 250,000 hectares (roughly 618,000 acres).

At Gleba, riparian and Indigenous populations work with extractivist activities as well as family farming. Because the soil is rich in minerals, like bauxite, mining companies are also active in the region.

The area has been defined as an environmentally distinctive settlement because of its biodiversity and the communities that live in the region. That’s why land titleship has to be treated as a collective subject, not individual, like the government wants. The entanglement is quite old, and hasn’t been resolved yet.

The Bolsonaro Administration mixes up the provisional titles for land settlements and talks as if it were all permanent. The provisional titles are nothing but use permits, a kind of acknowledgement that occupying the land is legitimate. But that changes nothing for the farmer.

Raoni Rajão, UFMG PROFESSOR

A provisional land grant doesn’t change the life of the small farmer

Another problem with the expedited land grants is that, according to specialists, the land grants are either provisional or merely a renewal of documents issued in past years. In practice, the document doesn’t allow the farmer to, for example, get bank loans or sell the land.

“The Bolsonaro administration mixes up the provisional titles in land settlements and talks as if it were all permanent. The provisional titles are nothing but use permits, a kind of acknowledgement that occupying the land is legitimate. But that changes nothing for the farmer,” explains Raoni Rajão, a professor at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG).

A survey carried out by the Amazônia 2030 initiative shows that during the Bolsonaro administration (2019 through 2021), 8,422 Occupation Recognition Certificates (CRO), a type of provisional title, were issued for parcels of federal public land in the Brazilian Legal Amazon region, outside of land reform settlement projects. During the same period, 1,307 permanent titles were issued in the region.

According to Silvério, one of the uses of this kind of provisional title is to collect taxes by charging the title holders. “Besides not investing in the creation of new settlements, the state will collect taxes through these property titles,” he says.

“Thus these provisional titles, lacking the value attributed to them during the campaign ads, add to the volume of paperwork at Incra, but are nothing other than a piece of paper that becomes a legal justification for the appropriation of land parcels in settlement projects,” Sauer concludes.

Still, according to the version that was praised by the president, MST (Landless Rural Workers Movement)—which has never been a part of any Brazilian government organ to date—is a key factor in understanding why his government did more for farmers. “MST has lost a lot of its strength because of the land grants. They didn’t grant any titles and kept the people enslaved. In three years, we’ve granted more titles than since the year 2000,” said President Bolsonaro. MST’s refutation of Bolsonaro’s statement did nothing. Messages sharing this version of the events were spread throughout public chat groups in messaging apps.

For specialists, the past couple of years should be deemed a setback. “Bolsonaro got elected promising ‘not one more hectare to Indigenous people’ and ‘no dialog with MST.’ The settlements were ‘practically emptied out’ and the budget for Incra and agrarian policies dried up,” says Sauer. “The dismantling started in 2016, or even earlier, with the number of settlements dropping and a smaller number of projects being carried out because of expropriation.

”This policy continued during the Temer (MDB) administration, in which the Ministry of Agrarian Development was made into a secretariat, which impacted the performance of agrarian policies and programs. In the second round of the 2022 presidential elections, Temer announced his support for Bolsonaro, only to take it back days later. He said he would support whoever “defends democracy, rigorously complies with the constitution, promotes peace, maintains the reforms accomplished during my administration, and proposes to the National Congress the reforms that are already on the country’s agenda.”

This report is part of the project Lies Have a Price (Mentira Tem Preço)—election special, produced by InfoAmazonia in partnership with the production company Fala. The initiative is part of the Consortium of Civil Society Organizations, Factchecking Agencies and Independent Journalism for the Fight Against Socio-environmental Disinformation. They are also a part of the Initiative the Climate Observatory (Fakebook), the Eco, the Pública, Repórter Brasil and The Facts.

Content is authorized to be republished if published in its entirety. Lies Have a Price is not responsible for alterations to the content by third-parties.