A scientist at Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research, with almost two decades’ research on the Amazon for, has carried out a ground-breaking analysis of how deforestation puts agricultural production at risk and turns Brazil into a driver of climate change.

Catastrophic. This is how researcher Luciana Gatti, of Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE), defines the current situation of the Brazilian Amazon. After nearly a decade of research with 18 collaborators, she has discovered that the largest forest in the world has not only lost its ability to capture carbon dioxide (CO₂) but has also become a source of emissions of the gas responsible for global warming.

According to the scientist, this is occurring mainly on the eastern side of the Amazon region and is driven by deforestation and fires. The findings, published last year in the journal Nature, left the researcher in shock. “It was very stressful for me,” she recalls. The news was picked up by media around the world and switched on a red light about how the country is deepening the climate emergency.

Since then, Gatti has been tirelessly undertaking the task of alerting Brazil to the seriousness of the situation in the Amazon region, made worse by record deforestation under the Bolsonaro government. In this interview with InfoAmazonia and PlenaMata, she explains how CO₂ is emitted by the forest and offers another important warning: deforestation in the Amazon is reducing the multiple environmental services provided by the forest. It affects the formation of rains and causes drought in some parts of the country, with disastrous economic and social impacts, especially for agribusiness.

This online interview was given from her home in São José dos Campos. “Here I can meet a part of my work demands without having to release CO₂ into the atmosphere through unnecessary travel to my laboratory. And I still help INPE to save electricity”, jokes the chemistry PhD.

We can see that everything is interconnected. The place with the greatest deforestation is also the place with the greatest loss of rainfall. And this loss happens with greater intensity in the dry season.

Luciana Gatti, INPE scientist

InfoAmazonia – How long have you worked at INPE and been following the Amazon?

Luciana Gatti – I’ve been taking measurements in the Amazon for eighteen years. However, in 2003 when this work started, I was at IPEN [Institute for Energy and Nuclear Research]. Later, in 2014, the idea arose of our laboratory becoming the National Greenhouse Gas Laboratory and thereby establishing an official monitoring network for Brazil. But the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MCTI) wanted us to be part of an institute more concerned with the environment, which would naturally be INPE. So, the negotiations that followed led to IPEN transferring the laboratory to INPE and thus we came here in 2015.

In 18 years of studying the Amazon, what kinds of change have you observed in the region apart from the increase in deforestation?

We have observed a reduction in rainfall, an increase in temperature and greater carbon emissions from the forest. We also observed major differences between the four regions that we were studying in the Amazon. For example, the emission of carbon, which is a natural forest process, is greater in the southeast and northeast than in the southwest and northwest.

We didn’t understand this difference until we calculated the forest cleared in each of these areas and it all made sense. We saw that the greater the deforestation, the more emissions occur. Then we started to study temperature and rainfall, because we also observed variation among the regions. Then we realize that everything is interconnected. The place with the greatest deforestation is also the place with the greatest loss of rainfall. And this loss happens with more intensity in the dry season.

How important is this loss of rain?

The northeast Amazon, which had been 37% deforested by 2018, has suffered a 34% reduction of its rains during the burning season, in August, September and October. And in these months the temperature has risen by almost two degrees over the last 40 years. The southeast, the second most deforested region, with a 28% forest loss, has lost 24% of its rain and the temperature has risen by 2.5 degrees. The dry season in these regions has become drier, hotter and longer.

So, by deforesting we are putting rainfall at risk?

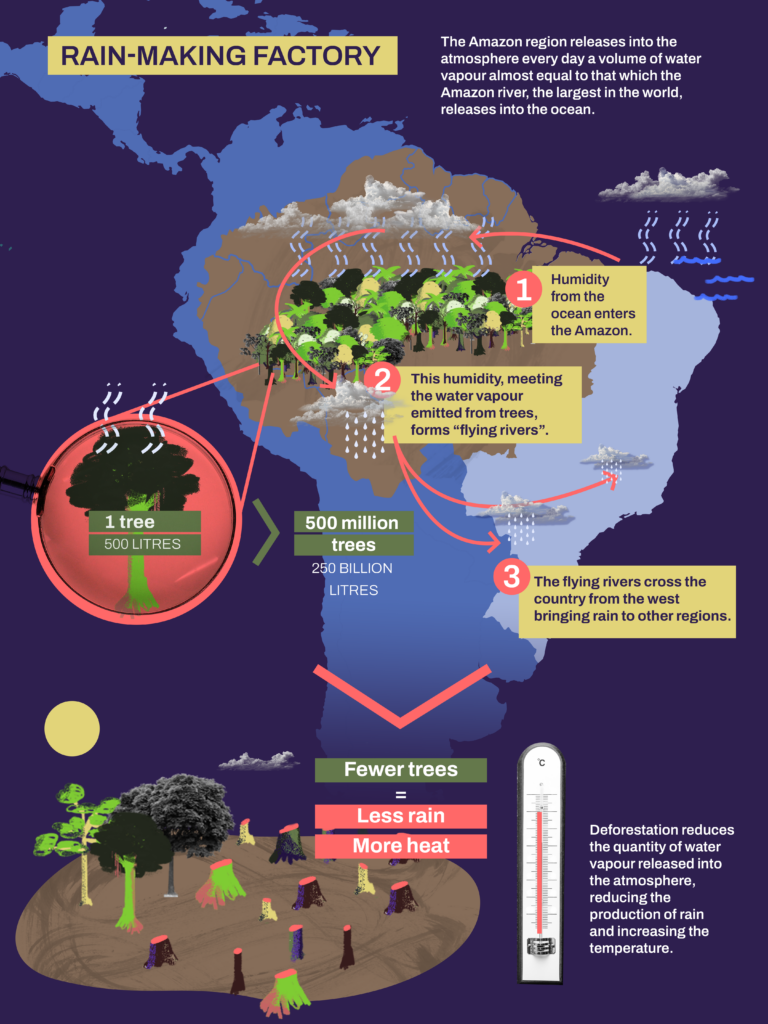

Exactly. We are destroying our rain factory. To give you an idea, the Amazon releases every day into the atmosphere a volume of water almost equal to that which the Amazon river, the largest in the world, releases into the ocean. That’s a lot of water! Trees capture liquid from the soil and releases this into the atmosphere in the form of vapour. This is an extremely important system for the formation of rain. In addition, the mass of air coming from the Atlantic Ocean and entering Brazil along the north coast brings the humidity that causes rain, and you need to replace this water vapor for it to continue raining along the trajectory of this air mass. This replacement takes place in the forest. But we have already deforested 20% of the Amazon and so the replenishment of water vapor in this air mass is decreasing in the most deforested regions.

In addition to producing rain, what other environmental services does the Amazon provide to Brazil and the world?

The Amazon serves to protect against climate change, because, in addition to producing rain, it reduces the temperature. To take water from the soil and release it into the atmosphere in the form of vapour, the tree needs energy. It thus takes this energy from the environment in the form of heat, causing cooling. Imagine a grove of trees. It’s cool and pleasant, right? Now think of this grove with all the trees cut down. What do you think will happen to the temperature? It goes up. This is what happens in the Amazon and everywhere else. In addition, the forest absorbs carbon, which also helps to contain climate change.

When you add together natural emissions and those from degradation, we have more CO₂ released than the forest has the capacity to absorb. We are turning the Amazon into a driver of climate change.

However, according to research led by you, this process of carbon absorption has decreased. Tell us a little more about these results.

What we say is that part of the Amazon rainforest has become a source of carbon emissions. First, we need to understand that the forest not only captures, but also naturally emits CO₂. Imagine a tree undergoing photosynthesis. It absorbs CO₂ from the air, and the carbon from that CO₂ will be incorporated to form its trunk, branches and leaves. At night the tree breathes and releases some of this CO₂. The forest is dynamic, there are plants growing and dying, so you have a second natural source of emissions, which is the decomposition of dead vegetation. There is also the emission of soils breathing, whose peak occurs in June and July. But humans, by deforesting and burning, potentialize these emissions even more.

In other words, the sum of emissions is greater than the capture?

Yes. This is already happening on the eastern side of the Amazon. Until 2018, the northeast captured only 20% of total emissions. In the southeast the forest is dying rather than growing. It works like this: after they deforest, humans burn – and this burning usually spreads into the forest that has not been deforested. At first, we have the emissions from burning, but after the fire goes out, that part that was burnt dies slowly and continues to be a source of carbon. When you add together natural emissions and those from degradation, we have more CO₂ released than the forest has the capacity to absorb. We are turning the Amazon into a driver of climate change.

What Brazil has done in the last three years in terms of degradation is going to cause a generalised agribusiness failure.

How serious is this overall scenario for Brazil and for the planet?

This is very serious for Brazil because it rapidly and directly undermines our climate. Rivers are drying up and areas in the centre of the country are turning into deserts. Secondly, the Amazon affects South America. The drought in the Pantanal causes problems for Argentina and Paraguay because it is a hydrographic basin there that supplies these countries. And given the size of the Amazon region, it is obvious that it has an influence on the entire world. It is heating up to the point of having uncontrollable fires that kill people and burn cities. There are sandstorms and extreme rainstorms that cause massive flooding.

How is our daily life affected by these changes?

Food becomes more expensive, because agriculture is an activity that depends on the climate and suffers from these impacts. And it is the farmers themselves who are driving the deforestation of the Amazon. Electricity also becomes more expensive. In fact, life gets more expensive for everyone. With higher temperatures and longer periods without rain, we have drier air. We need a certain climatic state in order to be healthy. So, this is a scenario of extreme discomfort. More people on the planet are dying today from heat waves. It hasn’t arrived here yet because we have the Amazon. We have been given a huge divine gift and, in our stupidity and ignorance, we are destroying that gift.

So, does this mean that agriculture is the main culprit for the degradation while at the same time directly suffering its impacts?

Exactly. I have a colleague who calls this “agro-suicide”, because farmers have caused enormous damage to their own agriculture. The problem is that they are not the only ones who will pay for this. What will happen to our agriculture? It will rain much less in the dry season; in the rainy season there will be big storms, which also cause crop failures. You can even have hailstorms, high winds and lots of water, which also kill the crops. Agriculture is an important part of our economy, but it depends on essential weather conditions. This is where the role of ecosystems for climate control comes in. We will need to develop other strategies, because what Brazil has done in the last three years in terms of degradation is going to cause a generalized agribusiness failure.

We need to get to zero deforestation throughout Brazil by next year. We have to have the political will, because the catastrophe was sown during the current administration.

How do you reverse this scenario?

The greatest wisdom lies in humans interfering less with the planet. But we’ve already interfered more than we should. So, we will have to give back to nature part of what we have taken from it and practice more sustainable lives. We should eat less beef, which needs a very large area of deforestation, as well as water and giant soy and corn plantations for feed. Do we really need to eat cattle? Can’t we have other sources of protein? It is also not sustainable to use coal and oil. Brazil has ethanol. Let’s use more ethanol. We will have to develop technologies to replace current habits, otherwise life on Earth will become increasingly difficult.

Are you hopeful?

I am hopeful for change. And for a government with greater wisdom. We need this, otherwise there will be a terrible catastrophe, because we are planting a catastrophic future. We must act fast. How much we can slow this down is hard to know. It will also depend on the political will to try to compensate for part of the destruction that has occurred during the Bolsonaro government. In 2020, 24 trees a second were cut down in Brazil. This is crazy. What we’ve done in Brazil for the last three and a half years is insane. We need to get to zero deforestation throughout Brazil by next year. We have to have the political will, because the catastrophe was sown during the current administration.

What is it like doing science under the Bolsonaro government?

Very difficult, because you are seen as an enemy. What is going on? People need knowledge to make decisions. It’s not a matter of opinion. If you try to build a house by yourself, it will collapse on your head, because you don’t have the knowledge to build the base and the foundations. You need someone who has studied to make the decisions. Those in power do not need to have the knowledge. But they must have the wisdom to consult those who do. Thus, the specialists provide the information and armed with this, they are able to take better decisions for the community.

Interview by InfoAmazonia for the PlenaMata project.