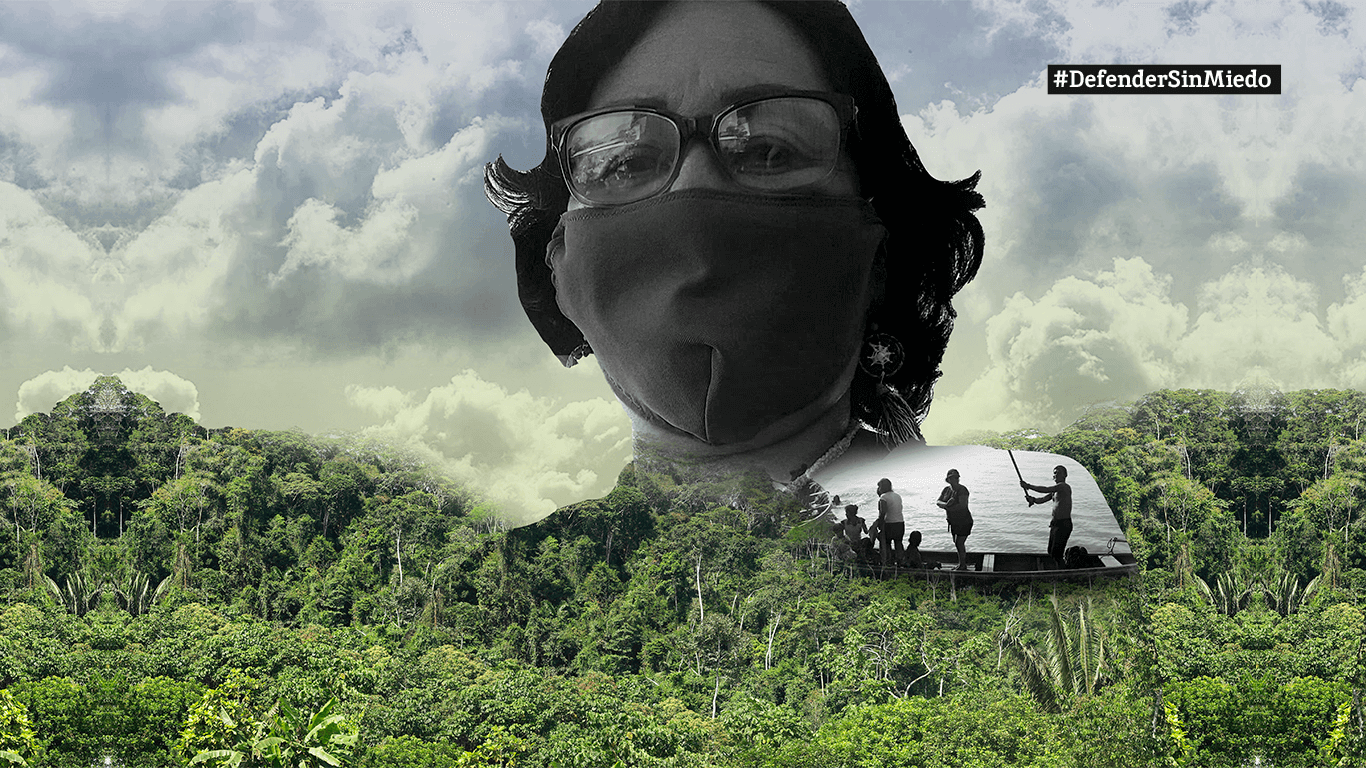

Rosa Aranda faces two miseries. One in her own body: she was infected by Covid-19. The other is the historical pollution generated by the oil industry, which threatens the territory in which she lives, Piwiri, in the Ecuadorian Amazon forest.

By Paola Jinneth Silva

Four years ago, Rosa Aranda Cuji, an indigenous Kichwa national in Ecuador, decided to take the lead as an Amazonian woman who is resisting the extraction of oil from her ancestral lands. Her greatest pain, she says, is that for thirty years this activity in the upper basin of the Villano River has made her people and the jungle sick.

This leader tells me over the phone that she is concerned about her health, because it has taken her longer than usual to recover. “I have not been able to rest; my job as a leader is full-time,” she says. Rosa knows she has Covid-19. Her husband is still dealing with the effects of the disease, her three children have recovered, and her community, living in the midst of the jungle, also suffers from the virus. Working out of Piwiri in the municipality of Moretecocha (in the Pastaza province of eastern Ecuador), she hopes to be better soon and, eventually, will have to continue to face the worst ‘disease’ of all: the one that is destroying her jungle and she blames on the oil company.

The Body | The Land

Rosa is 40 years old. She is a woman with small eyes and long, graceful hair, much like the rivers of her land. Her hair is the bluish-black color characteristic of Amazonian women who groom their hair with wituk, a fruit from which a dye is extracted that also can be used as face paint on special occasions. Rosa tells me she lives in Piwiri, a community of seventeen families with seventy people in all, including boys, girls, women and men, both young people and adults. She is the president of the Sumak Kawsay Association, which comprises 150 families from four villages (Rayayacu, Tarapoto, Kamungui and Piwiri) out of nine that make up the Moretecocha commune of the Kichwa people.

Rosa’s work is important because she lives at the gateway to the Amazon, on what the oil land register refers to as Block 10 (map), a territory that encompasses an area of 200 thousand hectares of jungle crossed by the Villano River, which separates Moretecocha from Curaray Parish. This region is located in the upper sector, at the mouth of the Lliquino River, which Rosa says brings pollutants from the Villano A and B oil field and the pipeline that carries crude to the Triunfo Nuevo processing plant. The Arco Oriente-Agip Oil consortium arrived in the area three decades ago (1988). In 2019, it was acquired by Petroandina Resources Corporation, which is part of the Pluspetrol Group.

Today, what worries Rosa is that the company already has a foothold in Moretecocha, thanks to the Landayacu exploratory well. And, if extraction is allowed, the road likely will be expanded, as will the logging of balsa (a type of wood found in the area), hunting and the environmental degradation of tropical forests that function as essential carbon sinks. The company’s entry into the area also would pose a physical and spiritual threat to the indigenous Kichwa, Shuar, Ashuar, Waorani and Sapara people.

Symptoms | Arrival of the Oil Company

“When the virus started, I had a high fever. It lasted three days and three nights, with a high temperature. First, I was treated with medicine for the flu, to make sure my lungs were not affected,” recalls Rosa, who has demanded more from her body than she should ever since fulfilling her role as a leader. She says people asked her to leave the area because, if they got sick, who was going to help them?

“The government operates in the cities, but not in the jungle,” Rosa says.

This is why one of her routine duties as a defender of the environment is to travel to Puyo, the capital of Pastaza, and sometimes to Quito, the nation’s capital, to tell the world what is happening in her part of the jungle. “I can no longer stand by and see so much pollution destroying our rivers and the diseases in my territory. That hurts,” she says.

If Rosa is to leave the area, she has two possibilities: one is by plane from Piwiri to the Río Amazonas airport in Shell (an airline ticket costs about 380 dollars, which is almost equivalent to the minimum monthly wage in Ecuador). The other option is to ask someone from her community to transport her in the Association’s canoe for four hours up the Villano River to Curaray (Rosa must guarantee fuel and oil for the round trip, which costs about 10 dollars). Once there, since the road to the jungle ends, Rosa must take a three-hour bus trip to Shell, a town 20 minutes from Puyo. This adds another 15 dollars.

Rosa works for the governing council of her Moretecocha commune as a secretary. However, she earns her living as an independent accountant, thanks to professional studies she completed in 2012 at the Universidad Regional Autónoma de los Andes in Puyo. Her work as a leader is unpaid.

Her community has no permanent government-sponsored health service. Whenever there is an emergency, the locals are obliged to contact the doctor at the health post in Curaray by radio. Since Piwiri is not in favor of the oil company, its communications are cut off, because the antenna that connects it to that health center belongs to the company. “They say it is damaged, but that’s not true, since it works for the other communities,” says this leader. In online meetings she has called out the Ecuadorian Ministry of Health for allowing her community’s right to be manipulated in this way.

For Rosa, the health of her jungle is tied intrinsically to that of her people. Living in the Villano basin, they eat fish that are contaminated because of the oil well, and their “chagras” (crops) suffer from blight. “Papaya is almost extinct and the cassava has fungi. We cannot call this development, sumak kawsay (good living in Kichwa) is having our water clean and our forests healthy, rather than money,” says this defender.

The latest environmental impact study on activity in Block 10 (where the Ecuadorian government authorized oil exploration and extraction) was presented in 1989. Conducted by an evaluation commission with delegates from the government and indigenous groups, it had already warned of serious deterioration in the vegetation, due to deforestation; the presence of toxic waste discharged directly into the soil and water; damage to hunting and fishing; and stomach and skin diseases. As explained by Carlos Mazabanda, the field coordinator in Ecuador for Amazon Watch, a non-governmental organization that supports the communities in southeastern Ecuador, “These effects were just from exploratory activity.”

“We live off the river; it gives us our life and our crops,” emphasizes Rosa, who goes on to point out that infections, particularly among women, are constant and there have been cases of cancer because it is risky to drink the water or wash in the river. Three years ago, an NGO known as Acción Ecológica accompanied a health brigade from the Skin Specialization Center and found that 80 percent of the population had some type of skin condition. According to community accounts, when it rains, the oil company’s treatment plant overflows and the waste ends up in the Lliquino River, which flows into the Lipuno and Villano tributaries from where Rosa’s community gets the water it needs to live.

The accusations regarding pollution and disease are being investigated by the Office of the Ombudsman of Ecuador. His representative in the province of Pastaza, Yajaira Curipallo, says the complaints are not limited to the expansion of Block 10, pollution problems, the rights to nature and to prior and informed consultation; they also deal with the company’s intent to drive a wedge between the indigenous nationalities in the region by offering privileges as a way to fragment and weaken their criteria on protecting nature. By October 2020, the investigation led by that office is expected to announce whether there have been violations committed by the company.

The Disease | Discord

Ecuador has fourteen indigenous nationalities. These are original ethnic populations organized in communion with the land. Rosa belongs to one of the eleven nationalities that inhabit the more than twelve million hectares that make up the Ecuadorian Amazon, which the State has divided up under a petroleum land registry system (indicating which areas are eligible for bidding, exploration and exploitation). According to data provided by Acción Ecológica, 63 of the 71 blocks in Ecuador are in the Amazon, and 32 of those 63 are in operation. This situation has prompted local communities to request action to protect their territory, such as the decision handed down by the Pastaza Court of Justice granting protective action to the Waorani people in April 2019 because the government did not consult with them before granting the concessions.

According to Andrés Tapia, communication director for the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities in the Ecuadorian Amazon (Confeniae), Rosa’s case is not unique. She is part of a network of leaders who function “as a single body to prevent expansion of the extractive frontier in the Amazon. We are concerned about the fact that oil companies remain active in the midst of the pandemic, disregarding security measures, and the national government intends to rely on oil activity to remedy the economic crisis in the wake of the pandemic, ” explains Tapia, adding that the situation once again violates the rights of local communities and their leaders, who have been criminalized for defending nature (charged with alleged crimes such as terrorism, sabotage, attacks and resistance).

For Rosa, all the problems in the region can be traced back to the work of oil companies. “For 30 years, all they did was to create a dependency in every sense. So now, there are people who cannot imagine the future without them.”

Acción Ecológica maintains that working with indigenous communities to defend the jungle has been a challenge. Felipe Bonilla, a consultant for this NGO, says Agip Oil historically fulfilled the role of the state, freely influencing decisions on the education and health of local inhabitants. He likens it to blackmail, since “they provided benefits such as health promoters, medicine and school snacks in exchange for extracting oil and polluting the land.” Bonilla, who helps to guide the effort to strengthen community leaders in the southeastern part of the Amazon, adds that some people are in favor of the company for this reason and, therefore, “leaders like Rosa are demanding the State assume its responsibility so as to free the community from that dependence.”

Rosa also knows that in the jungle you need to eat and generate income, but she suggest it can be done in a clean way. “I know we have the ability to establish alliances and consider a form of development that does not destroy nature,” she says. For Mazabanda, from Amazon Watch, it is difficult to advance in the protection of tropical forests without economic, social and cultural support, and he is concerned the situation will become even more complicated because these populations are exposed to a triple threat: natural disasters due to climate change (e.g., the humanitarian crisis at the beginning of this year due to the floods caused by heavy rains), the oil company and, now, the Covid-19.

Even so, Rosa has not lost hope. Her goal is for her community to grow stronger in the next two years, so as to not allow the company to open up more wells. “I really want to work, because I am indigenous and I know the sad reality of my people. If it is in my power to support, manage, talk and demand our rights from the State, I will. I will continue to do so until the end,” she says with pride, recalling the company had planned an environmental impact study for the Landayacu well at the beginning of 2020, but her commune blocked it, arguing that it was a process without prior consultation.

The Cure | Making the medicine

Regarding her treatment for Covid-19, Rosa says two medicines are important: the first is a western one to attack the Covid-19 virus as soon as possible; the second is her own medicine to avoid the aftermath of the illness.

According to Confeniae monitoring data on Covid-19, the Kichwa community of Pastaza had reported 399 cases of contagion and five deaths from coronavirus by September 13, 2020. Although no one in Rosa’s community had died from the disease by the time this article was written, she is still vigilant. “I call to ask how things are going, and they answer me via a satellite phone; [it’s] a high-frequency radio that works with a solar panel. They tell me ‘masks’ give them a headache and children have to be pampered to convince them to take natural remedies, because plants are usually bitter,” she says. Rosa also indicates she has been told people cannot isolate because the care is community-based. If someone gets sick, it is better to stay together. If not, “they will die of loneliness.”

Their own knowledge has been her community’s salvation. Rosa says female and male elders are guiding the younger ones on how to prepare medicines, and the women with knowledge of plants meet to talk about what remedies have worked and how to prepare them, according to each person and their symptoms. “Mingas (community work sessions) are conducted to gather, prepare and apply our own remedies to overcome the disease. They send them to me as well,” says Rosa, who is even encouraged to see the positive side of the situation: “This virus has allowed communities to understand that protecting the forest is useful; they value the forest, our medicine is there, and it is our life as a community.”

“I think I’m going to overcome this,” Rosa tells me in an optimistic tone as we end our call. She shares a photo with me on WhatsApp that shows her sitting on her heels in wooden house beside a pot filled with plants she collected with her son on the outskirts of the town of Shell, so he can learn as well and be able to help his father with his steam baths. “My back hurts sometimes, but I hope to improve so, when I return to my community, I can take a trip along the Conambo River and enjoy it as I did when I was a child.”

Recovery and Healing | The Land and the Body

In 2012, women began to assume leadership in the Amazon and to lend visibility to issues former leaders had never mentioned, such as sexual violence, prostitution, the change in men’s traditional roles, alcoholism, domestic violence and corruption, among other problems. A network of Amazonian Women was consolidated with individuals who defend nature, like Rosa. Many of them have received threats and accusations from the community itself, as has been Rosa’s case, because some people disapprove of their work as environmental defenders and have pointed out they receive money from activists. “It is a horrible situation. Fortunately, speaking to the community in our mother tongue (Kichwa) does help, but sometimes people believe we are attacking them if we say the oil company should not be allowed in. So, it is a constant effort, which makes it so important to educate and reverse the idea of depending on money,” says Rosa.

Mazabanda, from Amazon Watch, says, “These women who have dared to speak out about the impact of the oil companies are opening the way for others to join the resistance and to prevent an expansion in extractive activity in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Rosa Aranda has been working hard on that,” he confirms.

For this leader, working to defend the environment means breaking free of the notion that nature must be destroyed if people are to live. “It is why we are demanding the State provide education in our communities. That way, they can’t manipulate us and people will know there are different ways of living.” Convinced of this, Rosa has taken her three children to study in the town of Shell, so they can finish high school, since there is no secondary school in her community.

(Translation: Angie Caballero)

This article is part of #DefendWithoutFear, a journalist series that tells the stories of women and men who struggle to defend the environment in a time of pandemic. Developed by Agenda Propia, in coordination with twenty journalists, editors and allied media in Latin America, the series is made possible thanks to support from the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), a global NGO.