Brazil’s development bank is investing heavily in a plan to build huge hydroelectric dams in the Amazon and across South America.

More than 400 hydroelectric dams are already in operation, being built or planned for the Amazon basin and its headwaters, according to a recent study by anthropologist Paul E. Little. Together those dams, if completed, would impact five of the six main rivers draining into the Amazon.

Such a building frenzy, he writes, would constitute a “hydrological experiment” and create the risk of irreversible adverse changes to biodiversity and to the way of life of local inhabitants, especially indigenous people.

The proposed dams are a mixed bag. Some may be little more than pipedreams in the minds of bureaucrats, but others are serious projects. After a meticulous study, US scientist Philip Fearnside, from INPA (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia/National Institute of Amazonian Research), concluded that the Brazilian government had serious plans to generate electricity from all the main tributaries of the Amazon River east of the city of Manaus.

Until recently, the Brazilian government clearly planned to complete 19 of these dams by 2023, with a few already built — notably two on the Madeira River in the western Amazon basin and Belo Monte on the Xingu River. But a leaked copy of the government’s latest 10-year energy plan, obtained by the O Estado de S. Paulo newspaper, surprisingly showed that all the dams, except for the gigantic São Luiz do Tapajós hydroelectric project, have been discreetly removed from the planning process, for now.

The Amazon basin, it seems, will get a temporary reprieve from dam construction — a policy shift thought to be largely the result of the current disarray of the government due to the Lava Jato (Car Wash) scandal and possible presidential impeachment proceedings. However, there is no indication that the government has abandoned long term plans to follow through on the dams.

IIRSA begins to drive South American development

The government’s apparent pause in Brazilian dam construction does not however extend to its infrastructure construction efforts in other South American countries, especially in the Andean Amazon, where Brazil is advocating vigorously for dozens of new dams, some of extraordinary size.

Those dams are based upon recently forged international partnerships. In 2010, for example, the Brazilian and Peruvian governments signed an agreement, which would allow Brazil to build a series of very large dams in the Peruvian Amazon. As originally proposed, most of the energy produced was to be exported to Brazil to feed the country’s energy-hungry aluminium and extractive industries. The first five dams — Inambari, Pakitzapango, Tambo 40, Tambo 60 and Mainique — will cost about US$16 billion, most of which is expected to come from BNDES, the largest development bank in the Americas.

Brazil is also currently negotiating a deal with Bolivia to build a bi-national dam on Bolivia’s side of the Madeira River. There are additional plans to set up similar deals in Ecuador, Guyana, Paraguay and Venezuela, also BNDES funded.

All of these dam proposals have prompted concern from environmentalists and protests by local people.

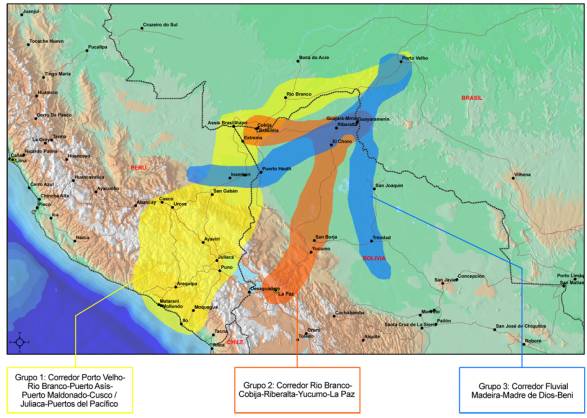

The proposed dams and other major infrastructure plans for the region are not one-offs. They are part of an ambitious scheme known as IIRSA (the Integration of the Regional Infrastructure of South America).

IIRSA would criss-cross the continent, including the Amazon and Andes, with a vast transportation and communication web — featuring highway networks, and improved waterways for moving crops and minerals; plus hydroelectric dams and transmission lines to power the extraction industry; along with a state-of-the-art telecommunication systems. This vast infrastructure grid is meant to connect isolated rural areas with the coasts, providing easy access to profitable natural resources (including timber and minerals) and crops (such as soybeans), for transit to urban and foreign markets, especially China.

BNDES is proud of the role it is playing in the initiative. “The BNDES, together with other financial institutions, has operated as a financier for infrastructure works that are part of the IIRSA initiative,” says the bank. “The projects are not only part of a strategy aimed at improving regional infrastructure, but they also play an important role, in particular, in Brazil’s economy. This is because financing exports is a federal policy and part of Brazil’s development strategy.”

Although IIRSA is officially touted as a promoting regional integration, critics say it is clearly a plan for improving export corridors for commodities — a plan that will largely benefit large mining companies, agribusiness and international grain traders, particularly those based in Brazil. It would also spectacularly profit Brazil’s giant construction companies, especially the Four Sisters — Odebrecht, OAS, Camargo Corrêa and Andrade Gutierrez.

A play for regional domination

IIRSA was originally proposed in 2000 by then Brazilian President, Fernando Henrique Cardoso. He launched the idea at a meeting held in Brasilia between 12 South American presidents and 350 Latin American businessmen. Cardoso enjoyed close relations with the US, and at the time IIRSA was seen as part of the FTAA (Free Trade Area of the Americas), President George Bush Sr’s overarching plan for turning the whole of the Americas into one giant free trade zone.

Then in 2003, the more nationalistic Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva became Brazil’s President. He immediately scuppered the FTAA, but IIRSA survived. Lula refashioned it as a tool for his radically new foreign political strategy. While accepting US hegemony in Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, Lula wanted to transform Brazil into a dominant regional power in South America and also on the world stage. IIRSA became part of Unasur (Unión de Naciones Suramericanas), a new South American body set up as an autonomous organization beyond the control of the United States.

Under Brazilian leadership, IIRSA expanded rapidly: from 335 projects, funded by a US$37 billion investment in 2004 to 579 projects, with a US$163 billion investment by 2014.

More than 70 percent of the funding for IIRSA comes from public sources, with a very large contribution made by BNDES. While many multinational companies will benefit, the scheme is now designed to fall under Brazilian hegemony, helping to fulfil its plan for regional dominance, say its critics.

A plan to market Brazilian goods to China

While Brazilian efforts to build large dams in the Amazon basin and in the Andes are being challenged everywhere, the dispute over IIRSA’s biggest project to date has been particularly fierce. It calls for the construction of a huge hidrovia (waterway-canal system), 2,600 miles long, which would permit barges to cross the notorious rapids of the Madeira River, creating a transport link with its main tributaries — Peru’s Madre de Dios River and Bolivia’s Marmoré River.

The plan requires the construction of four major dams, costing US$20 billion, with a major contribution coming from BNDES. When complete, the old dream of creating a transport link between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans will at last be realized — an enterprise first attempted in the early 20th century with the disastrous Madeira-Mamoré railway that cost the lives of 6,000 men. More prosaically, Brazilian exporters will be able to send grain, minerals, timber and other commodities down the hidrovia for shipment via Pacific seaports to China.

The Brazilian government pulled out all the regulatory stops to get the first two dams in this complex built — the Santo Antônio and the Jirau dams, both located within Brazil near the Bolivian border. In 2007, Brazil’s own environmental agency, Ibama, submitted a long report in which it refused on technical grounds to give approval to the preliminary licence for the two dams. The federal government reacted with fury, and Minister of the Environment Marina Silva caved in, sacking the head of Ibama’s Licensing Department, and replacing him with a more pliable official.

A few years later, the government was forced to take even more authoritarian action, dismissing Abelardo Bayma, the head of Ibama, after he sided with his technical staff, who had refused approval of the definitive licence for the dams because the conditions associated with the preliminary licence had not been met.

This tactic — of ruthlessly replacing recalcitrant government officials — was repeated a few months later when the government sacked the head of Ibama to get an operating license approved for the controversial Belo Monte dam in the Amazon. Dam expert Philip Fearnside has pointed out: “Since this pattern is capable of securing approval of any project regardless of impacts, it has severe implications for the many dams that have been announced for construction over the coming decades”.

Social organizations in Bolivia have also fought fiercely against the two IIRSA dams being built in Brazil, largely because of the Brazilian government’s refusal to carry out studies into the impact of the dams and their reservoirs on Bolivia.

In 2010, Bolivians lodged a complaint with their country’s People’s Permanent Tribunal, saying that the reservoirs for the Brazilian dams would have serious repercussions upstream in Bolivia, causing eviction of peasants and indigenous people, flooding large swathes of farm land and destroying habitat. They also warned of the severe risk of flooding in Bolivia, once the dams were completed.

The two Brazilian dams began partial operation in 2012 and 2013, and the fears of opponents were quickly justified. Early in 2014, Bolivia’s Amazonian region suffered the most disastrous flooding of the past 100 years. Some 75,000 people were impacted and a quarter-million livestock died, with economic losses of at least US$180 million. Some scientists blamed the severity of the disaster on a “reflux effect” by which floodwaters backed up behind the Brazilian dams and inundated Bolivian communities. Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff refused to accept responsibility, saying that it was “absurd” to blame Brazil for flooding that had resulted from extremely heavy rainfall — rains that are likely to become more extreme as climate change impacts worsen. An enquiry is underway. Such occurrences may demonstrate just how poorly IIRSA projects are being vetted for their detrimental long-term environmental, social and financial impacts.

IIRSA sparks more international conflict

There have been other clashes over IIRSA dams. In 2008, it became clear that Brazil’s largest construction company, Odebrecht, had botched the installation of turbines and conduction channels in the six-dam San Francisco hydroelectric complex in Ecuador, another IIRSA project, with majority BNDES funding.

With the company refusing to accept responsibility, Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa sent in troops to seize the dam and other of the company’s assets. The conflict escalated when Brazil withdrew its ambassador. The row was patched up, after Odebrecht agreed to pay US$48 million in compensation.

Popular movements have also successfully opposed Brazilian hegemony, most notably in Bolivia, where indigenous movements are powerful and a man of indigenous origin, Evo Morales, is President. In 2007, a Brazilian construction company, Queiroz Galvāo, was expelled for failing to comply with agreed-to standards in the construction of a roadway, another IIRSA project with BNDES funding.

In 2011, after indigenous groups had staged a highly successful march to La Paz that threatened to overthrow the government, Morales was forced to intervene and cancel a major highway project. The road was proposed to penetrate deep into Amazonian Bolivia and pass through the indigenous reserve and national park known as TIPNIS (Parque Nacional y Territorio Indígena Isiboro-Secure). This was a major IIRSA project, again with funding from BNDES.

In a report published in March 2016, three NGOs from three different countries — Conectas Direitos Humanos de Brasil (Brazil), Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Laboral y Agrario (Bolivia) and Global Witness (UK) — published an open letter in which they called on the BNDES “to ensure that the projects they finance abroad respect international legislation and that of the countries involved, as well as follow the Bank’s own norms, so that processes of genuine participation and permanent consultation with the people and communities are carried out, thus promoting a policy of prevention rather than cure.”

The letter was the result of a four-year investigation, in which documents were obtained through a Freedom of Information court action undertaken in Brazil. The NGOs found that both the Bank and Bolivian authorities were guilty of “numerous illegalities and human rights violations”, including failing to consult the indigenous communities to be affected by TIPNIS and failing to carry out environmental impact studies.

BNDES responded in a letter published in the Brazilian newspaper Valor Econonômico, saying that it had complied with all the social and environmental prerequisites “required for the signing of the contract” and that the Bank had respected the “legal and judicial standards by the Bolivian authorities”.

The NGOs were not satisfied by the bank’s response. Juana Kweitel, director of programs at Conectas, said: “if the Bank’s own policies, including those expressed in its Mission, Vision and Values, Social and Environmental Responsibility and Socio-environmental Policy, and Bolivian law had been respected, the contract would not even have been signed.”

Since the TIPNIS case, the Bank’s socio-environmental policies have been reformulated. However, the NGOs feel that the reforms have been insufficient because they do not include any concrete measures that would force decision makers to take decisive action to prevent human rights violations. According to Caio Borges, a lawyer working for Conectas, “this gap has not been filled and, until this happens, we [Brazil] will continue to run the risk of financing projects that are completely unsustainable from a human and environmental point of view, as was the case with TIPNIS.”

An uncertain future

Despite these setbacks, Brazilian construction companies continue to win scores of contracts for roads, airports and dams throughout Latin America, with Odebrecht benefitting most of all.

But that boom period may be ending, as the Brazilian government is destabilized and the economy is hobbled by the widespread domestic corruption scandal, accompanied by a significant slump in the global commodity market. According to Brazil’s Central Bank, the country’s economic output fell by an estimated 4.08 percent in 2015 and the OECD predicts a similar performance in 2016; this dismal economic performance may impede IIRSA plans.

In the longer term, there is another factor that may torpedo some IIRSA projects, especially dams — the escalating environmental crisis.

There is growing evidence that, unless global action is rapidly taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, climate change, aggravated by deforestation, will simply make it impossible to push ahead with some of the giant infrastructure projects. A 2015 government study says that Amazon basin river flows will drop drastically due to drought brought by global warming, and that the new dams’ reservoirs will hold too little water to drive electrical turbines, while parts of the Amazon will become too hot for agribusiness crop cultivation. Such forecasts will make it increasingly difficult to justify BNDES loans — floated with taxpayer money — for major projects that offer little hope of a high return on investment.

With climate change gaining momentum in the Amazon, the sixth great extinction well underway, and South America’s indigenous people struggling to survive, critics say that the restructuring of BNDES and a re-evaluation of IIRSA — adding up to a sweeping sea change — are more urgently needed than ever if South America’s natural biodiversity and cultural heritage are to be preserved.

Prospects

Such a change seems unlikely in the short term. The profound impact of the Lava Jato scandal continues to confuse and cloud Brazil’s political and economic future, as Brazilian political parties jockey for position and power.

The on-going investigation has already led to the arrest of top construction company executives on corruption charges, including the leaders of two of the Four Sisters companies — Brazil’s largest contractors. Marcelo Odebrecht, head of Odebrecht, has been sentenced to 19 years in prison for corruption, and Otavio Marques Azevedo, CEO at Andrade Gutierrez, has also been arrested. As the crisis intensifies, the legislature stands poised to start impeachment proceedings against Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff — with unknown repercussions.

The extent to which such upheaval will delay, or lead to the cancellation of Amazon and IIRSA projects is currently unknown. What seems probable, however, is that the current political unrest that is sweeping Brazil will continue for at least the next few months, and be on display for the world to see at the Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro.

It is important to note here that this six article series profiling BNDES has largely chronicled regulatory infractions and crimes linked to Brazil’s ruling Workers’ Party (PT). But this is so not because other political parties are blameless, but because since President Lula’s election in 2003, the PT has called the shots regarding BNDES loans.

What has become increasingly clear as the Lava Jato corruption investigation deepens is that the system of illegal bribes, kickbacks and inflated contracts permeates many of Brazil’s political institutions, and crosses party lines. A case in point: an astounding 40 members of the 60-member special committee that is deciding whether President Rousseff should be impeached have been accused of receiving “donations” from companies involved in the Lava Jato scandal. Eduardo Cunha, the President of the Chamber of Deputies, has himself been accused of corruption — of taking bribes and holding illegal bank accounts abroad.

Complicating matters even further is growing concern among Brazil analysts that the investigation into corruption is itself beginning to be used not to achieve justice, but for political ends. US investigative journalist Glenn Greenwald, who lives in Rio de Janeiro, commented recently: “Corruption among Brazil’s political class — including top levels of the PT — is real and substantial. But Brazil’s plutocrats, their media, and the upper and middle classes, are glaringly exploiting this corruption scandal to achieve what they have failed for years to accomplish democratically; the removal of [the] PT from power.” How a rightwing takeover of the government would impact BNDES, major infrastructure projects, ecosystems and indigenous people is unknown.

Most analysts expect real change in BNDES, if only because the ambitious projects it has funded at a heavy loss in recent years have become unsustainable for the country. Over the decades, successive governments have turned BNDES into an instrument for different — and often contradictory — policies, and this will certainly continue with new administrations. But until the current political upheaval is resolved, no one can say what form the next metamorphosis of the bank will take. Environmentalists in Brazil and across Latin America anxiously await further developments. With climate change racing ahead, there is a real risk, they fear, that while politicians fiddle, the Amazon will burn.

– This report was originally published in Mongabay and is republished by an agreement to share content.