InfoAmazonia’s deeply contextualized maps and reports aim to educate and involve the public in today’s pressing environmental issues.

by Claire Rigby

“The bathroom’s down the hall,” Gustavo Faleiros tells me, as we speak one June afternoon in his sunny São Paulo apartment. “But there’s no running water.” Residents of his building in the middle-class neighborhood of Pompéia have agreed to alternate water supply to their apartments—one day with and one day without—in order to eke out what trickles in from the water mains each day.

The São Paulo water shortage is bringing residents of Brazil’s biggest city face to face with environmental crisis inside their own homes. But for Faleiros, it has been part of his daily life for years. He is the founder of geo-journalism initiative InfoAmazonia, which uses data gleaned from databases and satellites to create innovative, deeply contextualized maps, graphics, reports, and features concerning the Amazon, covering burning issues facing the immense region—in some cases, literally: InfoAmazonia’s map of “heat focuses” shows the forest fires currently raging over the entire continent, updated hourly.

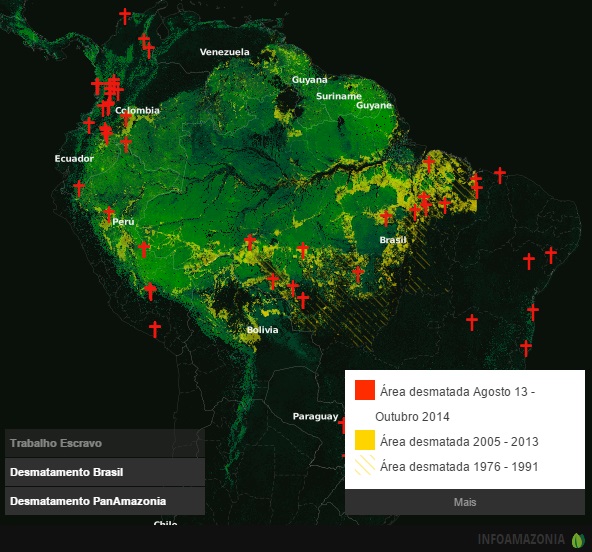

A dip into InfoAmazonia’s website reveals a wealth of interactive maps, which become ever richer as you enable layer after layer. In one, a map showing Brazil’s indigenous reserves is interlaid with another displaying the country’s environmentally protected areas, then layered with more depicting the ravages of deforestation, in color-coded historical phases. Another map starts with the same deforestation data, then surfaces the locations of slaughterhouses and timber clusters, and overlays those with red dots of varying sizes, pinpointing the locations and numbers of people rescued from slavery or slave-like conditions by the Ministry of Work and Employment from 2003 to 2013. The site’s data and mapping software are made available to the public, part of Faleiros’s commitment to increasing interest in the region.

“Our maps are not about just collecting and presenting raw data,” says Faleiros. “They are usually an integral part of a story, and sometimes even the starting point. What are enslaved workers doing in these areas?” He answers his own question—as, to some extent, do the maps: They’re removing roots after the felling of trees, burning scrub, making charcoal, and preparing the ground for cattle and later, perhaps, soya.

Faleiros, softly spoken and still fresh-faced at 37, has been working as an environmental journalist since 2001, when he graduated from college and joined the staff of the financial newspaper Valor Econômico. “I found environment stories immediately interesting,” he says. “And better still, there was no one covering it at the time—it was a space I could occupy within the newspaper.”

In a new phase for Faleiros and his team, InfoAmazonia has just initiated a Google sponsored project in two Amazon communities equipping local volunteers with sensors to monitor the quality of water for human consumption, whether delivered via the mains or drawn from wells. With this initiative, says Faleiros, InfoAmazonia is evolving from purely collecting, processing, and presenting information to becoming a primary source of information, generating relevant data using citizen journalists and communicators. “It’s about mobilizing and training people to monitor the environment around them, and to learn to collect usable data,” he says. “The possibilities around that are incredibly exciting.”

– This report was originally published in Good Magazine.