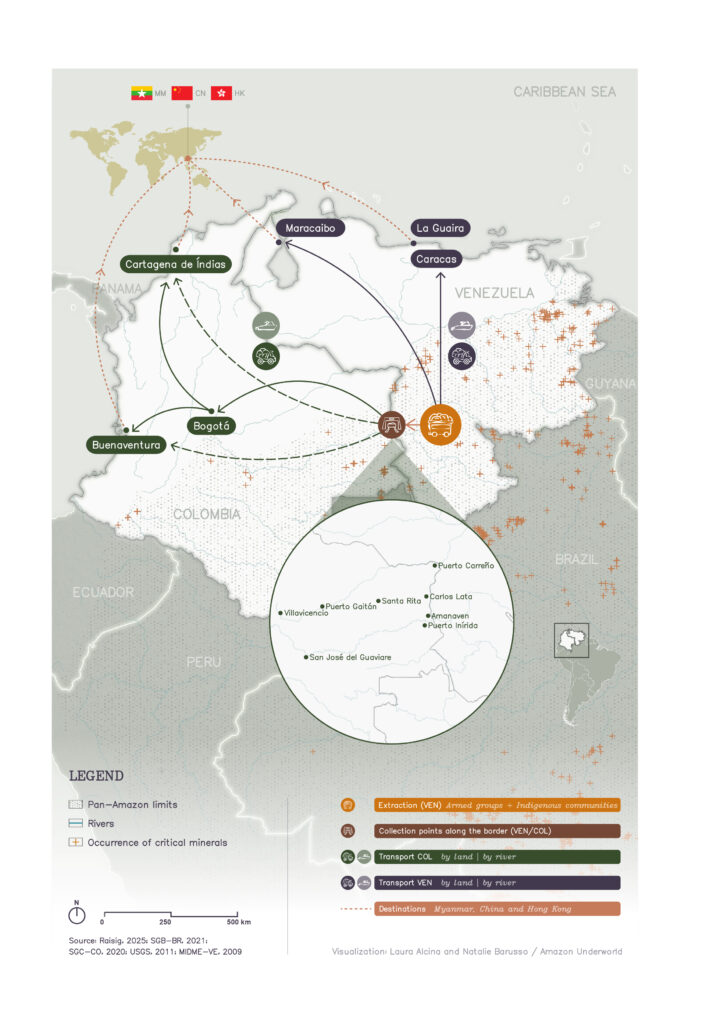

A complex network of actors has emerged around the critical minerals of the Amazon. Some operate along contested river corridors, trading with guerrilla groups and corrupt security forces. Others, under a façade of legality, move massive quantities of material through large port cities connected to international trade routes. Together, these operations endanger the environment and the sovereignty of entire nations.

The grayish-black sand and small stones sifted from river sediments and dug from pits across the Amazon hold little recognized value for local communities. Yet these materials are rapidly shipped abroad, where Chinese refineries process a wide variety of minerals and rare earth elements.

In Venezuela, much of the mineral output is first collected in centers operated by the Venezuelan Mining Corporation (CVM). Collection hubs for cassiterite and coltan in Los Pijiguaos and Morichalito, two nearby towns in the state of Bolívar, were established in 2023, after the Venezuelan government designated cassiterite, nickel, rhodium, titanium, and other rare-earth-related minerals as strategic resources for exploration, extraction, and commercialization.

In Morichalito, 10 CVM-branded collection centers remain active today. Two of them have documented export records to China and the United States. According to data from the Sicex trade platform and the transparency firm Sayari, large quantities of tin concentrate have also been exported through La Guaira Port, near Caracas, along with a major 120-ton shipment of niobium, tantalum, and vanadium concentrate — used in advanced manufacturing — through Maracaibo, in Zulia State, to India in 2023. From the CVM-registered centers, several exports to China were identified. Orinoco Global Group, registered in Puerto Ordaz, sent minerals to Ganzhou Ainuodeng Electronic in China. Inv. Mineral & Lab C.A. exported cassiterite to China (C&D Logistics, in Qingdao) CO. LTC and Traxys Europe S.A.

Guerrilla groups also buy and transport these minerals, often working hand in hand with individuals miners describe as “Chinese” buyers. A young miner explained: “When I was there I worked with tin. The buyers are there too: the same irregular groups, the guerrillas, and the Chinese.”

Other local miners and community members confirmed the same. “The Chinese are also buying stones. They’re together — the Chinese and the National Liberation Army (ELN). It’s no secret. They’re in it together. I assume they’re the same people because they eat together, buy material together, and even get off the helicopter together,” said a lifelong miner from the Cedeño municipality in Venezuela.

The People’s Republic of China currently controls 91% of the world’s rare earth processing capacity. Rare earth elements are found in many countries, but processing them is technically difficult, expensive, and highly polluting. China spent decades developing this refining capacity, granting it immense geopolitical leverage. Even when other countries extract rare earths, they typically must ship them to China for processing.

“I know they’re moving it by the ton into Colombia through Carlos Lata,” the miner adds, admitting he had worked for the ELN transporting minerals across the border. “I’ve seen everything. I’ve worked on it. I’ve carried it on my shoulder or with thick steel wire, loading canoes. Tons. I’ve filled canoes with tons, 15 tons, 20 tons in a canoe. I’ve made money when there’s work. … You have to do it.”

In Venezuelan territory, state forces reportedly cooperate with the Colombian guerrillas. “Everyone takes a cut because members of the National Guard are involved,” said one miner. “There’s the guard or the army, the Venezuelan Navy and the guerrillas … as if they worked for the same cause, you understand? So no one bothers the others. The guerrillas pay them a percentage. That’s what happens,” said a resident.

Another miner describes the transport process. “The government itself transports it in cars. The Sebin (Bolivarian National Intelligence Service) uses a white car without plates that says ‘official use only.’ There’s transportation for everything: coltan, tin, gold.”

Not all minerals extracted in Venezuela leave through official exit ports, where business is handled by state companies and foreign investors. Those seeking a larger slice of the mineral trade — including Colombian guerrilla commanders, ambitious state officials, and mineral traders — smuggle minerals through Colombia or via alternative routes that rely on air transport networks involving local communities and smelting operations.

In Colombia, transportation methods vary depending on geography and weather. During the rainy season, minerals move mainly by river through inland waterways that connect to unpaved roads leading to larger towns such as Puerto Gaitán, in the department of Meta, before continuing to Bogotá.

From Venezuela, the route crosses the Orinoco River, enters Colombia’s inland rivers and from there takes the land route, passing through Santa Rita, in Cumaribo municipality — an area larger than the Netherlands — and finally connecting via a road called “the 48” to Puerto Gaitán.

Traffickers and traders employ concealment methods along these land routes. Heavy sands containing minerals are hidden under thick layers of regular sand in trucks, making detection difficult during routine inspections.

In a joint operation, Colombian police seized more than 400 kilograms of smelted metals in Santa Rita, including 29 tin ingots, 36 bags of high-tin-content material, and smelting equipment. Tests showed the material had between 80% and 90% tin purity. The group captured in the operation were allegedly part of the José Daniel Pérez Carrero Front of the Organized Armed Groups–National Liberation Army (GAO-ELN) armed group and were turned over to authorities.

Before export, Venezuelan minerals are processed at various Colombian locations. Bogotá houses operations that smelt tantalum and tin into refined bars, transforming raw stones into metals that are easier to export and harder to trace to their illegal origins. In one case in Vichada, authorities seized a bar containing 80% tin and 20% rare earth elements.

Puerto Carreño has also become a significant processing hub. As one mining investor notes: “That’s why you find this phenomenon right now in Puerto Carreño. Foundries pop up everywhere, smelting tin, and the police do nothing.”

The final stage involves exporters operating through Colombia’s international seaports, mainly Santa Marta and Buenaventura. Instead of declaring materials under the appropriate tariff codes, exporters relabel them as ferro-tantalum, for example, effectively changing the classification from raw ore to processed material. This not only increases value but also reduces scrutiny.

A Colombian law enforcement official identified more than 40 customs codes that could potentially be used. “This is going to blow up in our faces, because it’s big,” warns the official. “Oversight by the DIAN (National Tax and Customs Directorate) is ridiculous,” he said, citing the lack of expertise for identifying critical minerals at Colombia’s exit ports.

Smuggling operations are supported by sophisticated financial networks designed to evade detection. Small transactions between cities like Medellín, Bogotá, and Villavicencio are deliberately kept below 10 million Colombian pesos (US$2500) to remain below detection thresholds. A Colombian intelligence official estimates profit margins between 5,000 and 10,000 percent, comparing it to “buying an iPhone for 100,000 pesos (US$25).”

GRACOR

Law enforcement officials, community representatives, miners, and mineral traders consistently identify Gracor as one of the corporate facilitators orchestrating this illegal trade. According to sources who requested anonymity for security reasons, the company maintains direct relationships across the entire criminal network, from the ELN and Segunda Marquetalia (a dissident faction of the former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – FARC) to individual miners and Venezuelan state officials.

A Venezuelan mineral trafficker interviewed by Amazon Underworld said: “Illegal operations buy and sell to these people. … Gracor doesn’t finance the resource, the irregular groups handle the money and negotiate with them. What we do is bring the merchandise to these groups and they negotiate with the Colombian company.”

To legitimize minerals from Venezuela, traders use sophisticated document fraud schemes. They exploit paperwork from subsistence miners — often from Indigenous communities — to make it appear that the materials were extracted in Colombia rather than smuggled from Venezuela. This practice exploits Venezuelan soil and resources, Indigenous peoples’ traditional mining rights, and the Colombian government’s efforts to formalize small-scale mining.

Despite frequent seizures, many confiscated mineral shipments remain in bureaucratic limbo for months. Some have even been returned to traders due to alleged administrative errors. Officials from four state agencies cited both suspected corruption and inadequate field training as contributing factors. Lina Beatriz Franco Idárraga, president of the National Mining Agency, admitted that authorities lack the capacity to distinguish legal from illegal mineral extractions.

Gracor registered a net profit of more than 311 million pesos (US$81,000) in 2024, according to documents filed in the Bogotá Chamber of Commerce, up 257 million pesos (US$67,000) in the last three years (2022-2024) — a nearly 480% increase in profits. Over the same period, its sales expanded by more than 14,700 million pesos (US$3.8 million).

In 2023, International Company Gracor SAS carried out two tin concentrate export operations, totaling 45,890 kilograms, according to the SICEX trade platform. In 2024, the company executed nine more export operations totaling 248,342.7 kilograms. During the first two months of 2025, three additional exports were completed, totaling 81,479 kilograms. During this three-year period, all exports were directed to Bluequest Resources AG in China. It should be noted that although the receiving company operates in China, Bluequest Resources AG is headquartered in Baar, Switzerland, with offices in Shanghai, China. According to the company’s website, Bluequest Resources AG is a leading commodity trading group specializing in the global physical trading of refined metals, minerals, and non-ferrous and precious metal concentrates.

Gracor denies all allegations. Alfonso Graffe, its legal representative, told Amazon Underworld during an interview in northern Bogotá that the minerals the company buys (tin oxide) come from Indigenous reserves and are the products of subsistence mining. However, Franco Idárraga insists: “That’s not subsistence,” referring to tin.

Camave

In March 2021, the Colombian Army seized 6,176 kilograms of strategic minerals on the Guaviare River, in Guainía department, aboard the “José Abel” vessel. The material included 196 sacks of coltan (columbite and tantalite) and 51 sacks of tin concentrate. An analysis by the Colombian Geological Service also detected uranium in samples, an element used in electronic components and nuclear weaponry.

The minerals belonged to Camave SAS, a Bogotá-based company founded in 2018 for mineral import and trade. The company operated without legal extraction licenses, fraudulently using a traditional mining formalization application that had been rejected in 2019 and whose holder had died. Authorities, even with overflights and satellite surveillance in the area, could not confirm visible mining activity in the declared extraction zones.

Camave SAS’s logistics operator collected minerals from Indigenous communities along the Inírida and Guainía rivers (Huecitos, Guamirza, San José, Vaquiro, Berrocal, and Maimachí), buying materials at derisory prices and without labor protections. Officials determined that the minerals likely originated from the ELN and the FARC dissident group Acacio Medina, both operating in the triple border zone between Vaupés, Guainía, Vichada (Colombia) and Amazonas (Venezuela).

The operation was financed by Mine Tres Inc., a Miami-based company owned by U.S. citizen Dan Boiangin, who provided an initial investment of US$300,000. The agreement allotted 80% of profits to Mine Tres Inc. and 20% to Camave SAS. Despite the 2021 seizure, Camave SAS continued exporting minerals until 2023, with China as the main destination.

In May 2025, Colombian authorities ordered the asset forfeiture of the six tons of minerals and the vessel. Ricardo Barrantes Balcázar, Camave SAS’s alternate legal representative, was sentenced in March 2025 to 14 years in prison for illicit enrichment, conspiracy to commit crime, document forgery, illegal exploitation of mining deposits, money laundering, and bribery. The case against Carolina Vargas Godoy, principal legal representative, remains under investigation.

THE BRAZILIAN EXPERIENCE

Unlike Colombia’s legal labyrinths and Venezuela’s conflict-ridden critical minerals landscape, Brazil has extensive geological data, despite its own history of Indigenous displacement and illegal mining. In 1970, the Radam Project emerged under the motto “Integrate So as Not to Surrender.” The initiative involved using military radar technology to systematically map the Amazon’s mineral deposits and natural resources. This mapping opened the region to prospectors and investors, providing Brazil with the detailed metallurgical maps that distinguish it from other Amazonian countries today.

100 kilometers from Belém, the capital of Pará state — host of the COP30 Climate Change Conference in 2025 — lies Barcarena. The city has been transformed in the last four decades, both by the aluminium industry and the Vila do Conde port complex. This industrial boom reshaped the urban landscape, as it became a key logistics and mining hub. Its population surged from 17,000 in 1970 to about 127,000 in 2020. Trucks now dominate the streets, and “evacuation route” signs mark neighborhoods near mining dams.

Between January and June 2025, the port complex handled 11.5 million tons of cargo, mainly inorganic chemicals (27%), including bauxite and soy. Outside the port, reality is harsher — red bauxite dust coats homes and streets, and rainwater can burn the skin.

According to Moisés Sousa Lopes, the president of the Union of Stevedores and Mineral Stevedoring Workers of Pará (Setemep), the port complex employs around 10,000 people, including 350 dockworkers. “Our job is to load and unload ship holds. We handle everything that comes in or goes out by water,” he said.

But Lopes seems far removed from the “energy transition” discourse. “What we understand is that mining isn’t just about energy — it also brings revenue for Brazil. The mineral travels by river and comes back as aluminum for export. It’s bidirectional. It provides energy and income — for the government and for Albras, the biggest aluminum producer in Brazil.”

Still, illegal cassiterite extraction continues within the Yanomami Indigenous territory. In Roraima state, the practice is carried out through networks managed by external investors, who provide falsified documentation to legitimize trade. The scale of operations is considerable, with an estimated volume of around 6 metric tons per river shipment and helicopter loads of up to 10,000 kilograms of ore. The mineral sells for between 60 and 70 reais (US$13) per kilogram in the city of Manaus.

The trade has become so normalized that even Uber drivers in Roraima are hired to carry sacks of cassiterite concentrate, showing how deeply these illegal activities have taken root. According to a Brazilian intelligence official, some mines are located in areas controlled by São Paulo crime multinational Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC). “There is cassiterite extraction at various points in the Indigenous Territory, including PCC controlled-zones in Waikás and Alto Uraricoera.”

The participation of criminal groups has transformed the cassiterite trade into a complex security operation. Brazilian authorities report that criminal factions not only control extraction areas but also provide protection services to miners, maintaining ownership of infrastructure and weapons. “There are areas and structures that belong to criminal members. They sell security,” said one law enforcement official.

Federal authorities have responded with Operation Ouro Negro, an initiative targeting fraudulent behavior that enables illegal mining. Investigators uncovered a scheme involving the State Environmental Foundation (Femarh) to facilitate irregular environmental licensing aimed at laundering illegally extracted minerals. In September 2025, the Brazilian Federal Police executed 13 search and seizure warrants in Roraima, Amazonas, São Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro, freezing more than 265 million reais in assets and suspending company operations.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), demand for critical minerals is expected to quadruple by 2040, intensifying geopolitical competition. China is leveraging its processing dominance through export controls; the United States is scrambling to rebuild domestic supply chains after decades of neglect; and the European Union has enacted the Critical Raw Materials Act to push for strategic independence.

These materials are now at the center of a new global contest, where technological power, economic security, and geopolitical influence converge. As competition over mineral supply chains heats up, the Amazon could soon become the frontline of the global energy transition — where illicit actors and companies outpace governments and researchers, aggravating conflicts over resource demand, Indigenous rights, and environmental protections.

China’s current dominance over rare earth elements has become a geopolitical flashpoint. In April, Beijing imposed export restrictions in retaliation for U.S. tariffs, weaponizing access to critical resources for defense, electric vehicles, and renewable industries.

The rare earth and critical minerals market has seen major price surges driven by China’s export limits, electric vehicle demand, inventory shortages, and global supply chain constraints.

The market has moved from speculative cycles to structural demand driven by the global energy transition. Global electric vehicle sales went from approximately 1 million units in 2017 to 17.1 million in 2024, generating unprecedented demand for rare earth elements used in electric vehicle motors and batteries.

This escalation triggered a global race to diversify supply, with Western countries seeking alternative producers in Africa and Southeast Asia. Access to these materials has become both a geopolitical priority and an economic necessity, impacting industries from consumer electronics to defense.

The paradox is clear: while nations race toward clean energy goals, the extraction of essential minerals is devastating communities and ecosystems in the Amazon. This connects global market dynamics and consumers worldwide to the fate of Amazonian populations and one of Earth’s most important climate regulators.

In its current state, critical mineral extraction not only destroys the natural environment but also finances violence and armed groups, including those designated as terrorist organizations, in conflict zones like Venezuela. Meanwhile, in Brazil, corporations are gaining legal mining titles on Indigenous lands in the heart of the rainforest.

The pressure is enormous. At least 188 Indigenous Lands are impacted by 1,286 critical or essential mining operations. Of the ten most pressured Indigenous lands, eight are located in Pará state, one in Amazonas and one in Roraima.

Sacrificing whole swathes of the Amazon in the name of sustainability is the paradox at the heart of the energy transition. This story connects remote Amazonian communities with global consumers with smartphones in their pockets and electric vehicles in their garages.

While the Chorrobocón community finds itself at the crossroads between gold and critical minerals, seeking to formalize but condemned to operate illegally; human rights violations worsen in Venezuela; and multinationals in Brazil seek to muscle in on the trade. Juan Guillermo García, the mining investor behind Minastyc in Colombia, put it succinctly: “Remember we’re in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, which is technology. And what do you need for technology? The raw materials.” When asked what will happen if no one brings order to the sector, he smiled wryly and said: “Welcome to the new Congo of Latin America.”

Opening image: Vila do Conde Port, in Barcarena. Photo: Luis Ushirobira/Amazon Underworld.

Researcher

Bram Ebus

Researchers

Daniela Castro, María de los Ángeles Ramírez, Emily Costa, Fábio Bispo, Hyury Potter, Karen Pedraza, Isabela Granados, Natalie Barusso

Cover and infographics

Laura Alcina

Maps

Natalie Barusso