In Colombia’s jungles, where the deep green of the Amazon collides with poverty and exclusion, a hidden and dangerous business flourishes. In the remote corners of Guainía, Indigenous communities such as the Puinave find themselves trapped in illegal mining, an activity that allows them to survive but threatens to destroy the land they inhabit. With the decline of gold, strategic minerals have risen as a promise for the future. However, this new mineral rush, which promises to be less polluting than gold mining, carries enormous environmental and social risks.

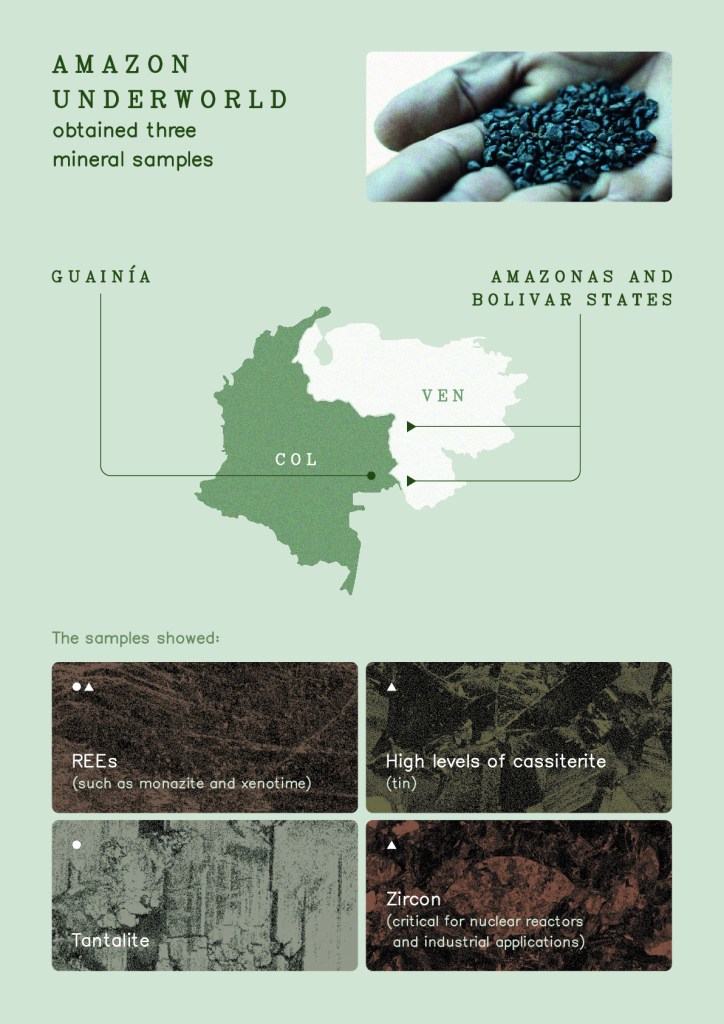

Amazon Underworld has spoken with Indigenous community leaders, miners, traffickers and traders, law enforcement officials, and geologists to gain a better understanding of this new mineral rush and its implications. Our team also received samples of so-called “black sands,” collected in Colombia’s Guainía department and Venezuela’s Amazonas and Bolívar states. This concentrate contains some of the world’s most sought-after critical minerals, hidden deep in the rainforest. When evaluated in a professional geological laboratory, test results indicated high levels of tin and tantalum, as well as monazite and xenotime, which contain rare earths.

Six hours from the Amazonian municipality of Puerto Inírida, in Guainía, lies Chorrobocón, an Indigenous reserve near the iconic Mavecure hills, a popular tourist destination. Chorrobocón’s main village is separated from direct access to Inírida by the Zamuro rapids, where locals risk their lives crashing their boats against waves and rocks, or hauling them along the riverbank. For heavy Navy vessels, the rapids act as a natural barrier, keeping them to the east, while Chorrobocón sits on the western side. From that point, the presence of former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) militants becomes more pronounced. These dissident groups are those who did not join the 2016 peace agreement with the Colombian government or deserted from that process.

The Puinave Indigenous community consists of a handful of wooden houses inhabited by about 750 people. Facing the community are three mining rafts with thatched roofs and processing equipment, moored along the riverbank.

“[Gold] mining is the only means or alternative for us to obtain, or through which we have obtained, a livelihood for our families,” said Luis Camelo, the village captain, after the evening evangelical service.

[Gold] mining is the only means or alternative for us to obtain, or through which we have obtained, a livelihood for our families.

Luis Camelo, the village captain.

When Brazilian gold prospectors arrived in the early 1990s, local communities quickly learned to build and operate their own mining rafts. Mineral extraction, including tungsten, gold, and silver, prospered in Zancudo, Cerro Tigre, and even within the Puinawai Natural Reserve. Since then, communities like Chorrobocón have sustained themselves through mining.

Carolina Florez Hernández, a shy woman with a soft voice, coordinates Chorrobocón’s Indigenous guard. She explained how mining has become intergenerational: “My mother worked in mining before I was born; I was born and raised there, I spent most of my childhood there, working with my mother… I am more than sure that our children will continue working in illegal mining, just as we are doing,” she adds with resignation.

Divers equipped with lead belts and compressed oxygen cylinders use hoses to suck sediments from riverbeds and extract gold. They descend, sometimes to depths of more than 25 meters, risking their lives. Underwater banks or slopes could collapse and bury them in the riverbed. However, gold mining may not determine the community’s future. The depletion of mineral deposits is a growing concern: “As the compañeros are saying today, gold production is no longer what it was. There were tons and tons that we would go to work on, but that’s all the stone that remains. I believe that in five years there won’t be anything left,” said Camelo, referring to the decline in gold yields, which is why the community is evaluating the exploitation of critical minerals as an alternative.

Miners pay 2 million Colombian pesos (US$500) for half a kilogram of mercury and use 300 grams to obtain 100 grams of gold. Aware of the environmental damage it produces, they hope the community can legalize these critical mineral operations. “If we manage to work those black sands… if they legalize it for us, we won’t work with fear. Because black sands don’t use mercury. If we had another economic source, we would stop illegal mining. We continue working because we have no other source of money,” said one miner.

While critical mineral mining is considered less harmful than gold mining, the associated environmental harm is undeniable. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, in Central Africa, coltan extraction has caused extensive deforestation and water contamination while destroying gorilla habitats in biodiversity hotspots. Similarly, rare earth mining in Myanmar, in Southeast Asia, has caused severe soil and water contamination through toxic chemicals such as ammonium sulfate, contributing to deforestation and the displacement of communities from contaminated agricultural lands.

Professor Thomas Cramer is a German geologist who teaches at the National University of Bogotá. Wearing a blue lab coat, he showed us his office, which looks like a small geological museum. Opening a display case of rocks, he approached a device that emits an alarm. “The thing is, health effects don’t appear immediately if the dose isn’t very high,” he warned, while the number on the screen kept rising — indicating radioactivity — the silent cause of diseases present in some minerals containing coltan. Health risks are nothing new for informal miners who work without protective equipment or training.

Alongside the unknown effects of low levels of radioactivity in some of the black sands, information is also lacking about which minerals Chorrobocón’s miners are finding. “Knowledge is power!” exclaimed Cramer, arguing that communities are part of a power imbalance in which global buyers know more about the minerals than those who extract them, a dynamic that even applies to the Colombian government. The National Mining Agency told Amazon Underworld that there is a lack of knowledge about the black sands and admitted that they cannot differentiate illegal minerals from legal ones when presented with samples.

In Chorrobocón, opening a plastic jar of fine dark-gray sand, Camelo said: “Right now I have it here, in front of me. It’s an unknown material at this moment, but we’re going to send it to be examined to find out if it’s valuable. We’re going to work.”

“If we find a buyer for black sand, we’re going to convert the same [mining] rafts that are dedicated to gold mining to working black sand,” he explained.

Unlike other Indigenous guard groups that patrol ancestral lands to prevent armed invaders or illegal miners from entering, Chorrobocón’s 20-member Indigenous guard protects its own illegal mining equipment. “The day the Army arrives to stop the [mining] rafts, the Indigenous guard will defend itself,” one guard member insisted.

In 1992, the Puinave communities in Guainía established an Indigenous Mining Zone covering almost 48,000 hectares along the Inírida River to formalize their gold-mining activities. The zone operated until its license expired in 2005, after facing legal challenges from groups such as the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC), which filed protective suits to prevent mining along the Inírida River. Since then, informal mining initiatives have flourished.

As a recognized Indigenous reserve with constitutionally protected autonomous self-government, the Remanso-Chorrobocón reserve obtained 13 collective mining titles from the Colombian government in 2021, but lacked the environmental licenses to legally exploit natural resources. Subsequently, in October 2024, the Colombian government issued a decree granting Indigenous authorities environmental powers within their collective lands.

In January 2025, the Remanso-Chorrobocón Reserve moved to withdraw more than 1,000 hectares from a protected forest reserve for mining activities. However, the Ministry of Environment denied the request, arguing that removals in reserve zones can only be granted for reasons of public utility or social interest, provided they do not harm the reserve’s protective function.

Community members perceive these imposed restrictions as paternalistic treatment. “We have the same needs as white people, the same ones as national government officials,” explained Camelo. “They receive their salary monthly, while we, the Indigenous communities, don’t have salaries. How is it possible that we suffer hardship here, on top of the riches? We have to work.”

Campo Elías Flores Hernández, a 50-year-old Puinave who runs mining rafts and has mined gold his whole life, explained the economic pressures. “Now we want the same food as white people,” he said. While riverside communities traditionally depend on fishing for their diets, acquiring meat is expensive in these remote Amazonian areas. “Previously we slept in hammocks, now on mattresses.”

Basic goods must be purchased in Puerto Inírida, a round trip that costs 2 million Colombian pesos, equivalent to US$500. Beyond yuca bread, the community doesn’t have much to sell. With mining money they have sent their children to study outside the territory. “That’s why we’re out there, risking our lives in mining,” said Campo Elías.

hat’s why we’re out there, risking our lives in mining.

Campos Elías Flores Hernández, the mining raft manager.

In order to preserve their subsistence model, communities like those on the Inírida River have developed protection strategies, including early-warning systems to notify about the presence of government police forces in the territory. “They already have someone on Mavecure hill with a radio who warns when they are entering,” explained a miner from Venezuela who previously worked on the Atabapo River and now works downstream from Chorrobocón. In addition to the community members who operate mining rafts, non-Indigenous miners, referred to by the community as ‘colonos,’ or colonists, entered the region to mine, often paying Indigenous authorities a share of their production.

Camelo, fully aware that mining is Chorrobocón’s economic reality for better or worse, understands that if they cannot legalize their operations or properly identify what minerals they have, they will be forced to sell on the black market — probably at prices dictated by risky traders seeking profits from illegal trade. “The company we talked to is Gracor,” said Camelo. “I understand that it is making an offer so we can work illegally.”

Opening image: A motorboat heads toward the Zamuro rapids, which separate Chorrobocón from the route to Puerto Inírida on the Inírida River. Photo: Bram Ebus/Amazon Underworld.

Lead Researcher

Bram Ebus

Researchers

Daniela Castro, María de los Ángeles Ramírez, Emily Costa, Fábio Bispo, Hyury Potter, Karen Pedraza, Isabela Granados, Natalie Barusso.

Cover and infographics

Laura Alcina

Maps

Natalie Barusso