By Eduardo Franco Berton

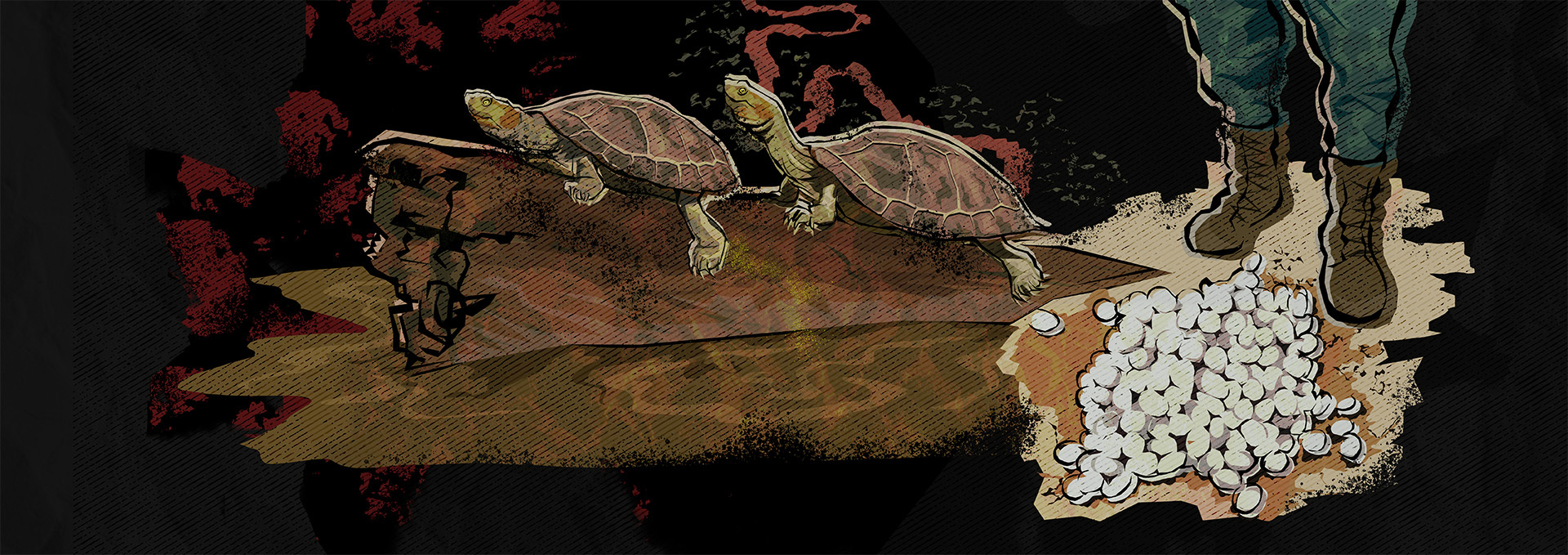

When the veil of darkness falls on the forest, men armed with .22 caliber Marlin rifles come with it, and they are determined to pursue their prey. Once a bullet hits its target, the injured animal falls into the water and has to swim to the shore, where it bleeds to death. “If they don’t catch it with their hands, they will shoot it dead. “That’s how you hunt yellow-spotted turtles,” Samuel whispers to us. That is what we will call a police officer who is familiar with these operations and asked not to be identified. He is aware of the danger that lurks in this remote region of the Bolivian Amazon.

Samuel speaks about people who are after the water turtle, locally known as peta de río (Podocnemis unifilis). It is considered one of the most hunted species in the Amazon, whose meat and eggs are highly coveted and seen as a ‘delicacy’ by consumers from different places in the department of Pando and other border areas in the Amazon. From July to September, the rivers of Pando become a scenario of life and death. Yellow-river turtles undertake a several-mile journey to the beaches of the Tahuamanu, Orthon and Manuripi rivers, where they bury their eggs in the warm sand, continuing their natural cycle. But their arrival does not go unnoticed. Dozens of people venture through the waters of these rivers and their beaches to extract the eggs of those reptiles.

Each foray by the hunters is like a dance with death, driven by the ambition to obtain as many eggs as possible. “They jump into the water at dawn and swim to the other side or cross it on inner tubes. Then they begin to collect (the eggs); they finish with a beach and cross to the other bank of the river. At that crossing, they can be attacked by a black caiman or a sicuri (anaconda), or step on a manta ray,” says biologist Rolando Toyama, Natural Resources technician at the Manuripi Reserve.

Driven by the promise of high profits, smugglers face these imminent dangers and constant persecution by the authorities, and they are not content with extracting turtle eggs from one nest – they loot up to 50 nests at a time. Each nest has 30-35 eggs, and their value on the black market reaches five times the price of chicken eggs.

They jump into the water at dawn and swim to the other side or cross it on inner tubes

— Rolando Toyama, biologist and technician at the Manuripi Reserve

In the midst of this gloomy scenario, the yellow-spotted turtle is a ‘vulnerable’ species according to the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). To be legal in Bolivia, all wildlife trade, management or hunting must have a management plan, which exists only for the lizard and the vicuña. Therefore, hunting the yellow-spotted turtle is illegal.

Black market

Turtle hunters arrive quietly, as shadows in the night, from the turbulent waters of the Tahuamanu River to the apparent tranquility of Cachuelita, a community in the middle of the Amazon jungle of Pando, where they carry out their clandestine transactions. “Then they spread the word that they have five or ten yellow-spotted turtles hidden under the engine of their boat. They arrive and sell them,” Samuel explains.

Smuggling of turtles and eggs in the Pando department and border areas

“There are about eight to ten little houses; [the place] where they do their business is located by the bank of the Tahuamanu River, and everyone goes there,” he says. Samuel reveals that when it comes to Brazilian buyers, the deal is closed in Real [Brazilian currency, BRL]. “They pay BRL 300 (USD 58) and get their turtle.”

For the officer, Cachuelita is a hot zone not only for wildlife trafficking, but also for other illegal activities. “It’s a key point both for drug trafficking and yellow-spotted turtle (trade). That’s where all illegalities take place. Drugs were seized there just the other day.”

But the black market for turtles and their eggs does not operate in a physical location. Samuel also explains that even home deliveries are offered on social media. “Yellow-spotted turtle eggs for sale. More information on WhatsApp” can be read in different ads published on Facebook buy and sell groups.

It’s a key point both for drug trafficking and yellow-spotted turtle (trade). That’s where all illegalities take place

— Samuel, police officer, about Cachuelita

Ximena Morales, a Biology graduate who has worked on projects with yellow-spotted turtles, says that egg trade in the municipality of Cobija, the capital of Pando, was quite intense in 2023, helped by digital technology. “It was spreading through WhatsApp, Facebook and Instagram groups. That is why the government provided emergency phone numbers for people to make the corresponding complaints.”

Historically, consumption of yellow-spotted turtle eggs in indigenous communities has been associated with obtaining proteins, says Julio Rojas, a senior researcher at the Amazon University of Pando. “Their consumption is more related to tradition and the fact that people have access to that food at certain times.”

Morales believes that migration to the cities and nostalgia for mountain products create demand on the black market. It occurs not only because of people who used to live in the communities and then moved to the cities, but also because of migrants from western Bolivia who move to Pando and are attracted by consumption of wildlife products. “These are the people who are creating most of the demand. Migration from other places has the strongest influence,” says Morales.

For this story, we consulted different people in Pando and they told us that yellow-spotted turtle meat and eggs have different uses: the eggs are eaten for their supposed aphrodisiac properties; the oil made from body fat is used in skin treatments and for hemorrhoids; the meat is an ingredient in the stew known as sancochado de peta; the shells are used as ornament; the eggs are used to make omelets and mushangué – a dish based on raw turtle eggs beaten with sugar and milk.

Under Bolivian legislation, wildlife cannot be captured, kept or locked up, and the same applies to subproducts. Likewise, the Criminal Code sets a penalty of up to six years in prison for destroying or damaging government property and national wealth.

Article 2 of Executive Order 03/2022, in turn, establishes an annual ban on turtle capture and hunting and egg collection in rivers, streams and lakes in the department of Pando, from July 20 to December 31 of each year.

Even with these laws and penalties, the thirst for yellow-spotted turtle eggs persists like a rebellious river that defies any attempt at containment.

Armed presence in Cobija

In the memories of the residents of Cobija, the violence unleashed between 2015 and 2018 still resonates like a ghost from the past that refuses to fade away. Researcher Julio Rojas reflects on those turbulent days when Pando’s capital became a scene of clashes between rival criminal gangs from neighboring Brazil, each fighting to claim their dominance over Amazon geography.

“You’d hear the news about clashes between gangs that were trying to occupy this territory. We no longer hear about that. Some of those groups have certainly consolidated their presence in this area,” says Rojas.

However, the shadow of crime still loomed over the city in 2022, with numerous cases of clashes between Brazilian criminal organizations Primeiro Comando da Capital (First Commando of the Capital) and Comando Vermelho (Red Commando) – both focused on drug trafficking. “Of course (they are present) right now in the Porvenir and Villaroja area,” Samuel explains with a mixture of concern and resignation in his voice. “These people have spread out everywhere.”

In April 2022, the Pando Parliamentary Brigade received a detailed report of Plan “Z” to fight crime by the Police of the department. The plan is triggered when criminal events impact the national territory, mobilizing Bolivian Police’s elite units. In this case, the strategy sought to confront the growing activity related to Brazilian criminal organizations such as Comando Vermelho and PCC. While Samuel points out that these two Brazilian groups are connected with illegal activities, our investigation could not establish their level of involvement with the smuggling of turtles and their eggs.

Smuggling routes to Brazil

In the meanders of the border area between Bolivia and Brazil, illegal trade weaves its threads in lonely routes that are almost imperceptible on satellite maps due to their narrowness. In these forgotten corners of the Amazon, stories of family clans specialized in various clandestine activities are interwoven. “Some members of the same family traffic on species while others traffic on substances (drugs), along the routes existing in the area,” Julio Rojas explains.

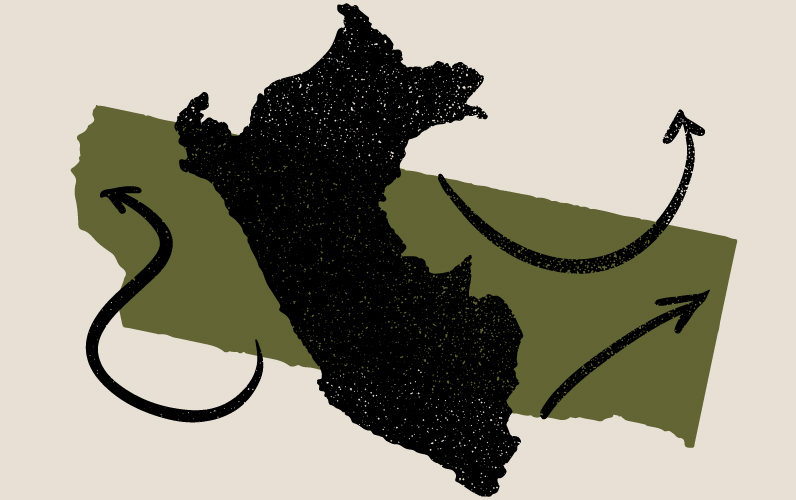

One of these places is the municipality of Santa Rosa del Abuná, Pando. Brazilian smugglers arrive there from the town of Capixaba (Brazil) and venture to cross this intricate border in search of their much-coveted loot – yellow-spotted turtle eggs. “They come at night in vans and head towards the municipality of Puerto Rico, and then they go to the Manuripi, Orthon and Tahuamanu (rivers),” says the police officer we call Samuel.

Kilometer 49 of the Puerto Rico-Cobija road is another access point. It is even possible to find these individuals camping there, on the beaches where they will collect their eggs.

Other little-traveled roads where the line between both countries blurs as dusk falls are in Cocamita and Frontineli, which become the perfect setting for these illegal operations. “At the border between Bolivia and Brazil there is a road. They come at night, do their business and move on to another point. In other words, there is no control, at night there is no control! Samuel complains.

Those interviewed for this report indicated that the final destination of these turtle eggs is Rio Branco, the capital of the Brazilian state of Acre, located 143 miles (231 kilometers) from Cobija.

These winding and under-controlled routes offer a direct path to criminal activity, where traffickers can operate with relative impunity. “These are specific paths for all illicit acts. For smuggling merchandise, for drugs, for everything, and also for eggs and turtles. We call these areas heavy zones,” says Samuel.

The smuggling route to Peru

Under the canopies of 40-meter Brazil nut trees that rise majestically toward the sky, we enter the Manuripi Amazonian Wildlife National Reserve, named after the Manuripi River, also known as the snakes’ river because of the winding horizon drawn by its course as it passes through the thick and impenetrable forest, seen from the camera of a drone.

In 2023, park rangers in the reserve spotted suspicious movements along the Sovereignty route, the diffuse border shared by Bolivia and Peru, another area where the law is just hearsay.

In this border area, yellow-spotted turtle eggs are a coveted commodity that changes hands quickly to continue their journey to Puerto Maldonado, where their price increases even more. “On the other side (of the Sovereignty route) is the Santa María community, already in Peru. From there, they follow the route to the Mavila community, one hour away from Puerto Maldonado,” says Luke López, a veteran park ranger of the reserve who is now its Chief of Protection.

Despite the presence of a military post, a police checkpoint and a Senasag (National Service for Agricultural Health and Food Safety) base, the Sovereignty route has earned a reputation as a red zone, a territory where, in addition to turtle eggs, timber and drug smuggling flourishes like weeds in the forest.

“The (Bolivian) people take (the eggs) to the Sovereignty area. There they sell them to others that take them to Puerto Maldonado. It’s already someone from Peru,” López explains. Last year, one of these incidents shook the tranquility of the Holanda community, when Peruvian smugglers were confronted by residents of the Manuripi River area, as recalled by local leader Roy Salgama. “They came from the Manuripi side (…) to get turtle eggs.”

Smugglers, who are skilled in the art of deception, have found ingenious ways to evade surveillance. Jute bags, cardboard boxes, mattresses, fishing nets, backpacks, coolers, among others, are used to camouflage and transport eggs and turtles – both alive and dead – to their next destination, where they will be converted into currency for those who profit at the expense of wildlife. Meanwhile, in their natural habitat, these animals play a key role in cleaning aquatic ecosystems. “Being omnivorous, they feed on a variety of remains, including some fungi, algae, river bushes, and decomposing fish,” Toyama explains.

Eggs seized in Manuripi

In 2023, three operations revealed the intensity of this clandestine trade. The first one took place on the banks of the Manuripi River, when 809 eggs were seized before getting to the Peruvian border. The man, caught red-handed, managed to flee and disappeared into the forest. “He left the eggs and ran towards the mountain, and could not be captured,” Rolando Toyama recalls with anguish.

The next two situations were no less worrying as more than 1,020 eggs were seized. The perpetrators assumed the legal consequences of their actions. “Apart from being sued for extracting the eggs, they were also charged with carrying an illegal weapon [a hunting shotgun] within the protected area,” said Toyama.

In another case, from 2021, a man was caught with 600 eggs and two turtles. The individual in question was brought to justice and sentenced to prison for his crimes against wildlife. “He was in prison for two years and then he was released on bail. His family paid it,” Luke López recalls. According to the Forest and Environmental Preservation Police (POFOMA), from 2021 to 2023, only six people faced some type of criminal charges for extracting yellow-spotted turtle eggs. The agency said that it does not have updated data regarding the number of eggs seized in the department of Pando in 2023.

A relentless fight

In the depths of Manuripi, harbormasters from the Bolivian Navy and park rangers join forces to fight elusive smugglers who move quickly and silently along the rivers.

“They use lookouts, men and women in the villages. When they see Bolivian Navy personnel together with park rangers, they immediately warn the smugglers by cell phone so that they can hide in the mountains,” says Frigate Captain Ángel Flores, head of the first division of the Pando Naval District, who has taken part in about 50 operations.

To fight that, law enforcement must act in the early morning darkness. “We enter by land, and then we take the boats (separately),” Flores explains.

With each turn of the calendar, Manuripi’s guardians must redouble their efforts, especially during the turtles’ spawning months. The clashes that take place in the guts of the reserve are monumental. With more than 370 miles (600 km) of rivers to monitor and only a few boats available, park rangers must employ ingenious strategies to control, monitor and inspect turtle spawning. One of these strategies is that of “volunteer park rangers.”

These community volunteers are mostly limited to filing complaints and accompanying routine patrols by land and water. However, their participation is scarce due to the absence of benefits or incentives to motivate them. Even though some 15-20 residents have been designated for this task, their support is inconsistent. “When we want their support, they disappear,” park ranger Roberto Pérez complains helplessly.

In addition, in an uphill race, just seven park rangers must cover more than 190,000 acres (773,000 hectares) of protected area, even though their Management Plan indicates that there should be at least 15. According to the IUCN, ideally, there should be one park ranger for every 2,500 acres (1,000 hectares). “We have five positions, but we only cover three, when we go to cover the next one, we leave the others unsupervised, and this way they can access any illicit activity,” says Pérez.

But the task is more than a simple cat-and-mouse game. The night comes with its own set of challenges. These defenders are in constant danger as the discovery of drunk and aggressive smugglers with firearms poses a threat to their safety. “They are armed with their shotguns and rifles. That makes the job a little dangerous,” says Luke López.

As a result of these pressures, yellow-spotted turtles are slowly fading from the waters of the Manuripi, right in front of the concerned eyes of those who monitor these lands and their wildlife. “We used to go down the river, and the beaches would be full of turtles. Now we observed that the turtles are in a critical state,” López complains.

A program to restore hope to yellow-spotted turtles

At the San Silvestre checkpoint, near the Peruvian border, in a refuge in the middle of the vastness of the forest, park rangers become the guardians of hope. There, among rustling leaves and river echoes, is a fragile and valuable treasure: more than 1,600 baby turtles waiting to be released into the waters of the Manuripi River.

The chelonians of this shelter are part of the Yellow-Spotted Turtle Monitoring and Conservation Program, carried out by the park rangers in coordination with the Amazonian University of Pando. The idea has germinated in the heart of the fight against egg trafficking and began in August 2023, not only to monitor and carry out seizure operations, but also to repopulate the rivers with the species. In a race against time before smugglers reach the beaches, Manuripi conservation officers have taken bold steps to collect the eggs and increase their chances of survival.

The task does not end with collection. They have made efforts to build an artificial beach in a safe place and under their permanent surveillance, where a new generation of turtles can emerge. The eggs are transferred with extreme care and precision to protect them from heat and rain during the journey to their new home. The program has already managed about 4,170 eggs. “We have had a hatching percentage of 88.3%. That’s a high value for us,” says Toyama.

In the palm of his hand, Luke López holds a two-inch (5 cm), four-month-old turtle, which is part of the program. The tiny chelonian has yellow spots that adorn its head, a dark, arched shell that shines slightly while its chest ranges from deep black to a yellowish hue. When it reaches adulthood, the animal will measure between 13 inches for males and 50 inches for females (5-20 cm), and will weigh between 20 and 26 pounds respectively (9 and 12 kg). Eggs seized from the hands of smugglers also end up here, even though they are not guaranteed the same hatching success because they have been handled. “But having a certain percentage of them born will helps us,” says Toyama, hopeful for the second chance these creatures will have to swim freely in the rivers, where they should remain.

Amazon Underworld is a joint investigation of InfoAmazonia (Brazil), Armando.Info (Venezuela) and La Liga Contra el Silencio (Colombia), Plan V (Ecuador) and the Environmental Information Network (RAI, Bolivia). The work is carried out in collaboration with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network and financed by the Open Society Foundation, the U.K. Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN NL).

.