Indigenous, African-descended and other traditional communities are caught in escalating violence from drug trafficking in Amazon “cocaine corridor.”

By Sam Cowie

Maria talks fondly about the peaceful rural community where she grew up. As a child, she recalls playing games in the forest and in the river with the other kids, picking fresh açaí berries and foraging for nuts under towering trees. There were no “industrialized toys,” she says. It was “all nature.”

But in the last few years, with the arrival of a group of drug-trafficking outsiders, that reality has changed to nighttime gunshots, police raids and talk of murder. Late last year, after a young man came to her home and threatened her, Maria* decided she had to leave.

“He said that if I snitched and had them taken out of there, I would bleed — my whole family would,” she says.

The man who threatened Maria suspected, correctly, that she had told local authorities about the criminal group’s activities. Fearing for her life, she fled the community called Sítio Cupuaçu, home to around 350 families, in Barcarena, a port city and today a major industrial hub close to where the Amazon River meets the Atlantic Ocean, in the state of Pará.

“We were terrified,” she says. “People who were born and raised here, we never heard of this drug business.” Her community is one of several quilombos — settlements formed by African people who escaped slavery in Brazil, and people of African descent — in the region.

Maria says the people invading her community claim to have “permission” from the leader of a local branch of Brazil’s notorious Comando Vermelho (CV), or Red Command, a drug gang with its main base more than 3,000 kilometers (1,864 miles) away in Rio de Janeiro. In the last five years, it has established itself as the dominant drug trafficking group in Pará.

The gang used the forested community as a distribution and storage point for drugs like cocaine, crack and marijuana, burying larger quantities in the ground in case of police raids.

Besides selling drugs, the CV also engaged in small-scale land grabbing, clearing land to divide into plots to sell and illegal construction, wrecking the community’s rich natural habitats.

“Trees that were hundreds of years old, they cut them down,” Maria said, showing pictures of fallen forest and foliage on her smartphone. “The animals left. It’s really sad.”

Drug flow through Barcarena on the rise

The northern port’s prime location near the mouth of the Amazon River offers better access to routes for both legal and illegal exports.

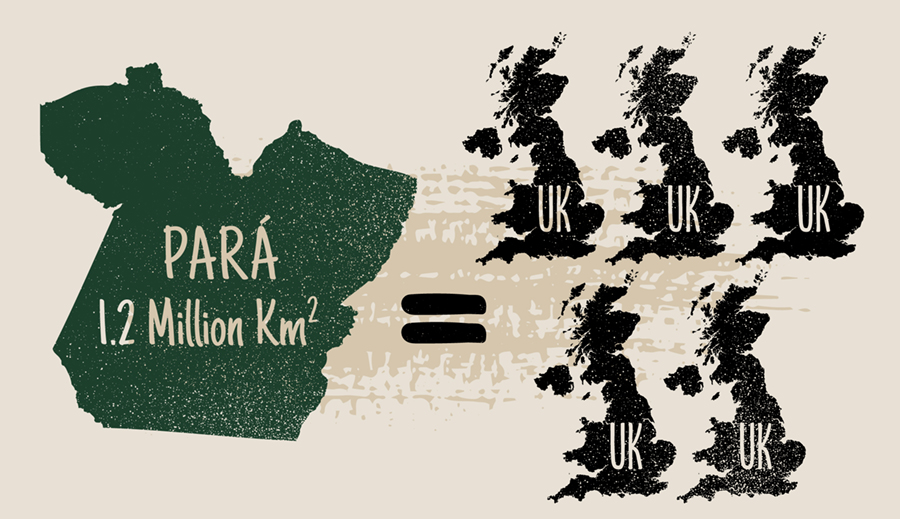

Traffickers bring cocaine into the vast state of Pará — which at 1.2 million square kilometers (more than 460,000 square miles)

IS MORE THAN 5 TIMES THE TOTAL LAND SIZE OF THE UNITED KINGDOM

— by river, highway or clandestine flights that have proliferated with an uptick in illegal mining in Pará and across Brazil’s Amazon in recent years

Both of the country’s main drug gangs, the CV and its more powerful rival, the São Paulo-based Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), or First Capital Command, have expanded their reach inside the state, experts say. Some of Brazil’s largest independent traffickers, such as Sérgio Roberto de Carvalho, known as “Major Carvalho,” a former military police officer accused of heading a major Brazilian drug-running network, and Karine Campos, known as the “Queen of Coke,” have operated there too, local reports suggest.

Once inside Pará, gangsters divide cocaine cargoes to send to domestic markets in the state or across the country, or to Europe using Brazil’s expansive port structures, including Pará’s Vila do Conde, a short drive from Maria’s house.

PRIME LOCATION FOR EXPORTS

The prime location of Vila do Conde port, just 120 kilometers (75 miles) from the Atlantic Ocean, makes it ideal for exporters sending commodities to Europe, China and the United States. In 2021, nearly 17 million tons of cargo such as soybeans, alumina, bauxite, fertilizer and corn passed through the port.

It is one of the so-called “Northern Arc” ports that gained prominence in Brazil over the last decade, which shorten maritime distances to key markets and therefore cut logistics costs, challenging the traditional dominance of São Paulo’s Santos port. But criminal organizations have also capitalized.

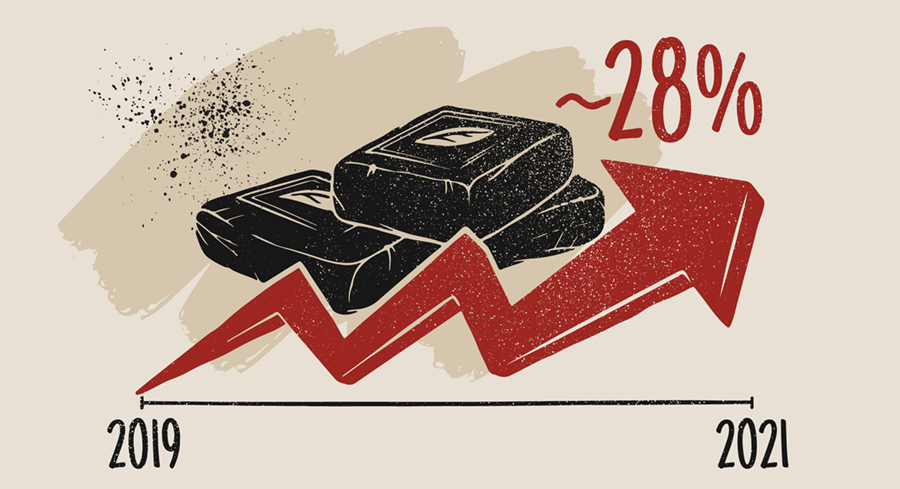

Data obtained through a freedom of information request by InfoAmazonia to Brazil’s federal revenue agency show that

THE VOLUME OF COCAINE SEIZED AT VILA DO CONDE INCREASED FROM 1,462 KILOS IN 2019 TO 1,870 KILOS IN 2021,

though experts have warned that seizures alone would not necessarily reflect an accurate picture.

In 2020, military police officers in Barcarena seized more than two tons of cocaine at a rural property a short drive from the port — and from Maria’s home — after exchanging gunfire with armed men who then fled into the nearby forest. At the time, it was the largest cocaine seizure in Pará’s history.

Then, in November 2022, federal authorities seized nearly three tons of cocaine hidden inside sacks of soybean meal at the port in a container destined for Portugal. It was one of the largest single cocaine busts ever recorded at a Brazilian port, according to local reports.

Authorities have also seized cocaine hidden in shipments of timber, açai and manganese, a mineral that has been increasingly coveted and extracted illegally in southern Pará in recent years by organized crime groups, ready to be exported or arriving from Vila do Conde to European ports in Portugal and Rotterdam.

While São Paulo’s Santos port is still the main exit point for cocaine headed to Europe, inspections have stepped up in recent years, forcing criminal groups to seek other ports, according to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)

“What we see is a very clear picture of the diversification of the use of Brazilian ports for the export of cocaine to Europe,” says Isabela Vianna Pinho, a guest sociology doctoral candidate at the Danish Institute for International Studies in Copenhagen and a member of the institute’s peace and conflict unit.

“This is down to a series of complex factors,” she adds. “There is the infrastructure issue, but at the end of the day, [international drug trafficking] relies on people and personal arrangements.”

The seizures at Vila do Conde reflect part of a reconfiguration of drug routes and exit points for cocaine passing through Brazil on its way to Europe, as well as the growing importance of the Amazon as an international drug transit point.

In the last decade, experts say, the volume of cocaine and other drugs passing through the Brazilian Amazon, whether destined for local markets or for export, has risen dramatically, with record production levels in Brazil’s neighbors Colombia, Peru and Bolivia.

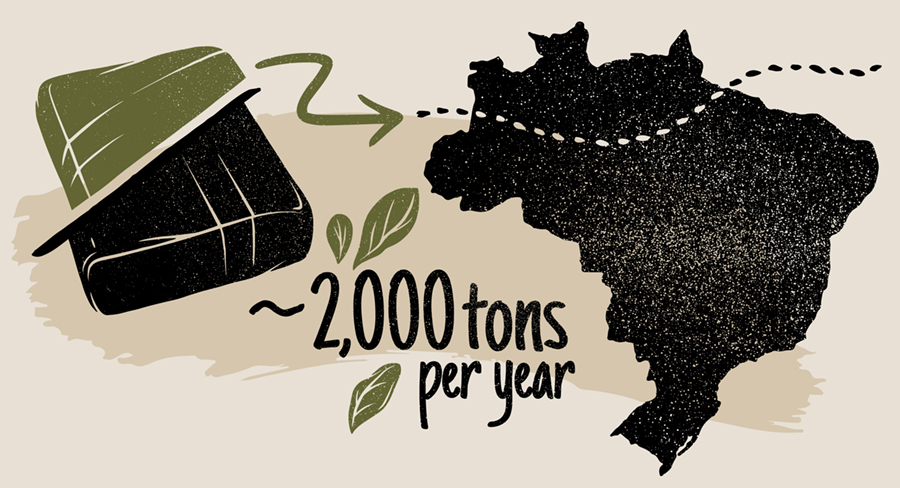

Approximately 2,000 tons of cocaine are produced annually, in Colombia, Peru and Bolivia.

ALMOST HALF OF IT PASSES THROUGH BRAZIL.

Just under half of the approximately 2,000 tons of cocaine produced annually passes through Brazil, roughly 40 percent of it through the Amazon region, according to Renato Sérgio de Lima, head of the non-profit Brazilian Public Security Forum.

“The turning point was in 2016,” he says, with the anti-aircraft machine gun murder of Jorge Rafaat, who controlled the supply of drugs on Brazil’s border with Paraguay, by the PCC, which then took over the route. “The Comando Vermelho needed to adapt and was forced to find new routes, reactivating old contacts it had with Colombian drug lords.”

While Brazil’s Amazon has always been violent, de Lima says, violence has exploded since 2017. The region offers various advantages to drug traffickers.

“It has less inspection and control, very cheap and exploited labor, and the possibility of exploiting various sectors of the economy in a much easier way than big cities,” de Lima says. He adds, “It’s much simpler there, because there’s less [state] supervision, so it’s very easy to launder money.”

CRIMINALS DODGE THE POLICE

In January, Amazon Underworld joined local military police officers in Barcarena on an operation to clamp down on drug trafficking and other crimes. Officers said that in recent years, the city had seen an uptick in gang members released from prison heading there to set up local chapters of crime groups like the Comando Vermelho.

Barcarena is home to several traditional rural quilombos like the one Maria fled, where officers say that gangsters from outside the city have sought to establish themselves.

The day before the operation, officers said they had raided a forest encampment set up by drug traffickers in the Itupanema Beach region of Barcarena. Across the city’s poorer neighborhoods, Comando Vermelho graffiti is omnipresent.

During the patrol, armed officers stormed a simple wooden house and arrested a man accused of rape who had fled from another city in Pará. Ultimately, however, the operation yielded no drug crime arrests.

One person present on the patrol, who requested anonymity, said that with the patrol ongoing, gang members would send the message round that police were out and therefore lay low. In April, police in Barcarena arrested a 34-year-old man wanted for homicide. During the operation, they also seized around 68,000 reais (equivalent to about US$13,600) in cash, as well as cocaine, crack, a .12-caliber shotgun, a .40-caliber machine gun, two .9- and .40-caliber pistols, and two vehicles.

Police allege that the man, whose identity was not revealed, planned attacks against security authorities during a wave of violence orchestrated by Comando Vermelho leaders last year in which at least seven police officers were killed. Shortly after, in July, 10 military police officers in Belém, the capital of Pará, were arrested on charges of kidnapping and extorting drug traffickers.

DRUG GANGS SPREAD BEYOND CITIES

Today, enrolled in a local program that provides protection and assistance for threatened activists in Pará, Maria laments the destruction of her community’s natural beauty and its social fabric.

“It was so good,” Maria says of the community. “We always had issues with grileiros [large-scale land grabbers] trying to claim our land, but they always backed off eventually when we showed them our land titles.”

She says the drug gang has also co-opted some community members and young people with small gifts and promises of easy money.

Her cousin, who was head of the local residents’ association, also fled the community after the gang threatened him with a gun at his house.

We’re good people who want to raise our children well. Now the best way for us to raise our children is to send them outside of the community

— Maria, a resident of the quilombo Sítio Cupuaçu

In 2019, a policeman was killed in the community, and one of those later arrested in connection with the murder had already been charged with international drug trafficking. Last year, two Comando Vermelho gang members were also killed there, in a raid that happened during the wave of attacks on police officers.

Maria said that the young man who threatened her at her home is the second in command in the area and handles sales transactions involving the clandestine constructions. She said his mother is from the community.

The gangsters removed the community plaque, so as not to put off buyers, and one of the threats Maria received came after she told a prospective buyer that the area was a quilombo, and that his purchase might later be revoked, as those lands could qualify for government protection in the future.

The person who came to her home “had a .38 revolver,” she says. Although they have not killed any community members, she adds, “They are always killing among themselves.”

“When the police come in, they disappear,” she says.

The dynamics of “invasions,” as illegal land occupations run by organized crime groups are locally known, are murky and often differ.

The Belém Metropolitan Region has some of the worst affordable housing provisions in Brazil, a country in perpetual housing crisis, so there is no lack of willing occupiers. One resident who lives next to a Comando Vermelho invasion in Ananindeua, another city in the Belém Metropolitan Region, says local gang leaders decide what lands can be invaded and by whom.

The tactic serves to further dominate and expand urban frontiers in a region where the Comando Vermelho’s only armed rivals are police and rogue police militias. Anyone who breaks the rules, by renting or selling without permission, for example, faces a “tribunal,” which can result in their murder or expulsion from the invaded area without compensation.

According to Aiala Colares Couto, a researcher with the Brazilian Public Security Forum and an expert on organized crime in Pará, the growing criminal movement in Barcarena follows a statewide pattern.

Gang leaders, known as torres, or “towers,” many recently released from prison or wanted by authorities, head to more remote locations outside of state capitals and city centers to avoid police detection.

“When they arrive, they need to maintain a relationship with drug trafficking, because they need to support themselves economically,” he says.

Couto says the CV in Barcarena would almost certainly seek to expand its influence in the port region, just as the PCC did years ago in São Paulo’s Santos port, where it now wields significant influence.

He said the CV spread rapidly in Pará, recruiting members within the state’s brutal prison system after Pará prisoners were jailed with CV members in federal prisons elsewhere in Brazil.

CV gangsters from Pará have also increasingly fled to Rio de Janeiro. Leonardo Costa Araújo, a gang leader known as Leo 41, was killed in March in a police operation that left 13 dead in Complexo do Salgueiro, in São Gonçalo, in the Rio Metropolitan Region.

The PCC, the CV’s main national rival, also operates in Pará, mainly in drug trafficking logistics, mostly in the south of the state. Recently, authorities raided properties connected to suspected lawyers of the group in the cities of Marabá and Castanhal. Smaller gangs, as well as several militia groups involving rogue police officers, also operate in the state.

What we see is the increasing suffocation of Barcarena’s traditional communities by both crime and heavy industry — the destruction of their traditional ways of life

— Cícero Pedrosa, a journalist and anthropologist who has studied Barcarena’s quilombos.

Besides rising crime, several major industrial disasters since 2010 have seriously damaged local habitats on which traditional communities depended.

In 2015, a Lebanese cargo ship headed for Venezuela with 5,000 cows and 700 tons of oil sank at the Vila do Conde port, killing most of cattle and releasing part of the oil into the river. Studies found the accident seriously depleted fishing stocks, damaging local livelihoods.

Three years later, residents complained to prosecutors that they suspected toxic leakage from the world’s largest aluminum smelter, owned by the Norwegian-financed company Norsk Hydro, had further poisoned local rivers, a claim later supported by studies. Shortly after, quilombo leader Paulo Nascimento was murdered. Lawyers and activists said his killing was connected to the complaint, but the company denied involvement.

“What we see is the increasing suffocation of Barcarena’s traditional communities by both crime and heavy industry — the destruction of their traditional ways of life,” says Cícero Pedrosa, a journalist and anthropologist who has studied Barcarena’s quilombos. “How can these families have a healthy life there?”

LAUNDERING MONEY THROUGH ENVIRONMENTAL CRIME

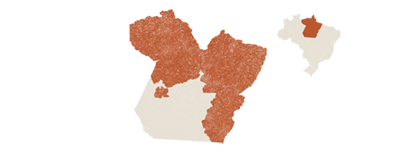

While Barcarena has emerged as a key drug trafficking hub, the CV has expanded even further in recent years into Pará’s vast interior, where violence has spiked. Today, the state is home to seven of Brazil’s 30 most murderous municipalities.

Jacareacanga, a hub of illegal mining activity and where the Munduruku Indigenous Territory is located, recorded a stunning 199 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants in 2021, the second-highest rate in Brazil and nine times the national average of 22 per 100,000.

Other municipalities in the top 30, including Floresta do Araguaia, Cumaru do Norte, Anapu, Senador José Porfírio, Novo Progresso and Bannach, also suffer from high rates of environmental crime and land conflict.

Today, drug gangsters in Pará and across the Amazon increasingly look to reinvest or launder illicit profits through environmental crimes such as wildcat mining, land grabbing, illegal fishing and poaching, which typically carry lesser penalties than drug crimes.

A 2021 police operation called “Narcos Gold” confirmed that criminals used gold mines in Pará as landing strips for planes transporting drugs and as a front for money laundering.

The main target of the operation, Heverton “Grota” Soares, held 18 prospecting permits for mining in Pará, which he used as a drug trafficking front, and is being investigated for drug trafficking, criminal organization, money laundering and homicide and has links to the PCC, according to media reports.

SHIPPING BY RIVER, ROAD AND AIR

Pará neither produces cocaine nor borders producer nations. According to state Public Security Secretary Ulame Machado, most cocaine and other drugs entering Pará, especially shipments bound for the port in Barcarena, come from the triple border with Peru and Colombia in neighboring Amazonas state and arrive by river.

“Skunk,” a high-grade form of marijuana produced in Colombia, sells in Brazil for five times the price of traditional, weaker weed imports from Paraguay and enables criminal groups already using the Amazon River route to increase their profits, he says.

Reports of such shipments headed directly for Brazil’s largest drug markets, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, have proliferated recently.

Machado mentioned a January seizure of 1.6 tons of cocaine and skunk hidden beneath 12 tons of prized pirarucu fish, from a vessel near Óbidos, in the Lower Amazon, a key region for the entry of drugs into Pará. From Óbidos, drugs can be loaded into trucks and transported by road, especially the BR-163 and TransAmazonian highways. From there, “you can deliver to the whole of Brazil,” including the Vila do Conde port, Machado says,

“It is much more profitable, much less risky for them to use Barcarena port,” he says. “And at the same time their logistics are much easier, because you don’t have to cross the whole country to get to Santos.” Bolivian cocaine passing through Mato Grosso also enters southern Pará by road, as well as by plane, he says.

An uptick in illegal mining in Pará in recent years, driven by record high gold prices, has increased the number of small plane flights, says Gustavo Geiser, an expert witness with Brazil’s Federal Police. “And since these guys are already doing something illegal,” he adds, delivering cocaine “is not a huge step up for them.”

Recently, Pará-born Felipe Pacheco, an illegal mining pilot from Novo Progresso, a notorious hotbed of environmental crimes like wildcat mining and illegal logging, was caught transporting nearly half a ton of cocaine in his plane in Mato Grosso state. He was found dead in jail days later, and his family believes he was murdered.

São Félix Do Xingu (86),

Altamira (83) and

Jacareacanga (53).

One of Brazil’s most experienced drug trafficking pilots, Silvio Berri Júnior, who worked for infamous Comando Vermelho leader Fernandinho Beira-Mar, held a gold prospecting claim in Pará and was arrested in 2020 on suspicion of working for mega trafficker Major Carvalho.

Machado says Pará also serves as an important base for traffickers transporting drugs by air to other regions of Brazil, as the vast state is often used for refueling stops. Indigenous territories in Pará, like those of the Kayapo and Munduruku, which suffer some of the worst destruction from illegal mining in the Brazilian Amazon, also serve as logistics points for drug flights, Machado said.

“Such places are convenient [for drug traffickers] because they are out of the way of the public eye,” he adds. “There are no police cars patrolling there. They are remote and isolated.”

In illegal mining towns and encampments across Pará, cocaine and crack fetch far more than the average street price — swaps of one gram of gold for one gram of cocaine are common.

DRUG TRADE ‘IMPOSSIBLE’ WITHOUT CORRUPTION

Machado says efforts are being made to stop the flow of cocaine into Pará, including the construction of civil police river bases in the Óbidos region and Abaetetuba, two key municipalities on the Amazon River drug route, as well as the recent construction of a base in Breves, in the Marajó Archipelago near the mouth of the Amazon.

The greater Belém area, where Vila do Conde port is located, consists of around 40 islands, many harboring “clandestine” ports where drugs can be unloaded. Barcarena itself is an island. Drug shipments pass by riverine communities and quilombos, Machado says, and authorities often find stashes buried in the ground in and around Barcarena.

Large quantities of drugs are spread out in smaller amounts in rural properties or warehouses that are cheaper and more protected because they are isolated. “But to enter the Vila do Conde port, it has to be professionalized,” he says.

Legitimate exporters may unknowingly have their containers hacked and filled by specialized criminal gangs working at ports, a technique known as “rip on/rip off,” when official seals are broken and then reapplied.

But “professionalized” drug shipments, like the 2.75 tons of cocaine found hidden in soybean meal in 2022, often require the help of corrupt public officials, experts say.

In July 2022, Pará state military police Lieutenant Aderaldo Pereira de Freitas Neto was arrested in Portugal, suspected of conspiring to have 320 kilograms of cocaine sent to Portugal from Vila do Conde port in containers of açai fruit. Marco Antonio Faria, a Barcarena based businessman, was also arrested when he received the cargo in Lisbon.

Armando Brasil, a Pará state military prosecutor, who officially requested Freitas’ removal from service, says international drug trafficking would be “impossible” without corrupt public agents. He notes that at the time the police lieutenant was arrested in Portugal, he was supposed to be on duty in Pará.

There are times when corrupt police know drugs are being kept somewhere, but they don’t say anything .They’ll just extort instead.

— Armando Brasil, Pará state military prosecutor

Brasil described a complex picture of warehouses used in the Barcarena area to store cocaine, often with the tacit permission of corrupt local police, and front companies set up solely to give an air of legitimacy to the drug trade.

“It is an institution to defend public order and morality,” he says of the police, “but unfortunately there are some who enter to steal, to extort to benefit themselves.”

‘WE HAVE NOTHING LEFT’

Investigations cited in local reports indicate that Freitas, the military police officer arrested in Portugal, worked for Portugal’s most powerful drug lord Ruben “Xuxas” Oliveira and Carvalho, the former military police major from Mato Grosso do Sul, then considered Brazil’s biggest independent drug trafficker.

Interpol agents arrested Carvalho, also nicknamed “Brazil’s Escobar” in a luxury hotel in Budapest in June 2022. Since 2017, according to local reports citing federal investigations, Carvalho had sent at least 45 tons of cocaine to Europe.

Karine Campos, nicknamed the “Queen of Coke,” a colleague of Major Carvalho’s and today considered Brazil’s largest drug boss, is also accused of leading a group of international drug traffickers that used the Vila do Conde Port to send cocaine to Europe. Currently she is on the run, sentenced to 17 years in prison for drug trafficking, along with her husband Marcelo Ferreira.

Meanwhile, back in Barcarena, a fisherman beaches a rickety wooden boat at Itupanema, a short drive from the Vila do Conde port, just as an intense Amazonian rainstorm begins. In the distance, hulking cargo ships stacked with steel containers filled with tons of commodities headed for international markets sit anchored as the storm beats down.

Maria understands little about the dynamics of international cocaine trafficking but knows the damage that has been inflicted on the forest community nearby where she was born and raised.

“We have nothing left,” she says. “If one day we manage to get this land back, we’ll have to start all over again.”

*Names have been changed.

Amazon Underworld is a joint investigation of InfoAmazonia (Brazil), Armando.Info (Venezuela) and La Liga Contra el Silencio (Colombia). The work is carried out in collaboration with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network and financed by the Open Society Foundation, the U.K. Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN NL).