Along border with Venezuela, Colombian guerrillas lure unemployed Indigenous youths into drug trade, extortion rackets and armed conflict.

By Bram Ebus

When men who had arrived in his small Warekena Indigenous village in a remote part of the Venezuelan Amazon offered him work driving a motorboat, Alexander* jumped at the chance. For the teenager, it was an opportunity to earn cash — a scarcity at the best of times, but especially since the economic collapse that had left Venezuela’s currency, the Bolívar, nearly worthless.

“They told me that I was just going to work, to support my family,” he recalls of the men who took him to a camp in the forest several hours away, where he stayed for two months. But there was a catch.

“When I wanted to leave, I couldn’t, because they told me I was already part of the group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia. That’s when I started guerrilla life,” he says.

“I brought drugs from Colombia to Venezuela,” Alexander adds. “From Venezuela, they distribute the drugs by plane.”

Sparsely populated and heavily forested, Venezuela’s remote southwestern state of Amazonas borders Colombia along the voluminous Orinoco River.

Photo: Bram Ebus

The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and National Liberation Army (ELN)

have long used the area to rest, move troops, hide kidnapping victims and receive medical care. After the signing of a peace deal with the Colombian government in 2016, dissident guerrilla groups began to increase their presence in the Venezuelan Amazon.

Photo: Bram Ebus

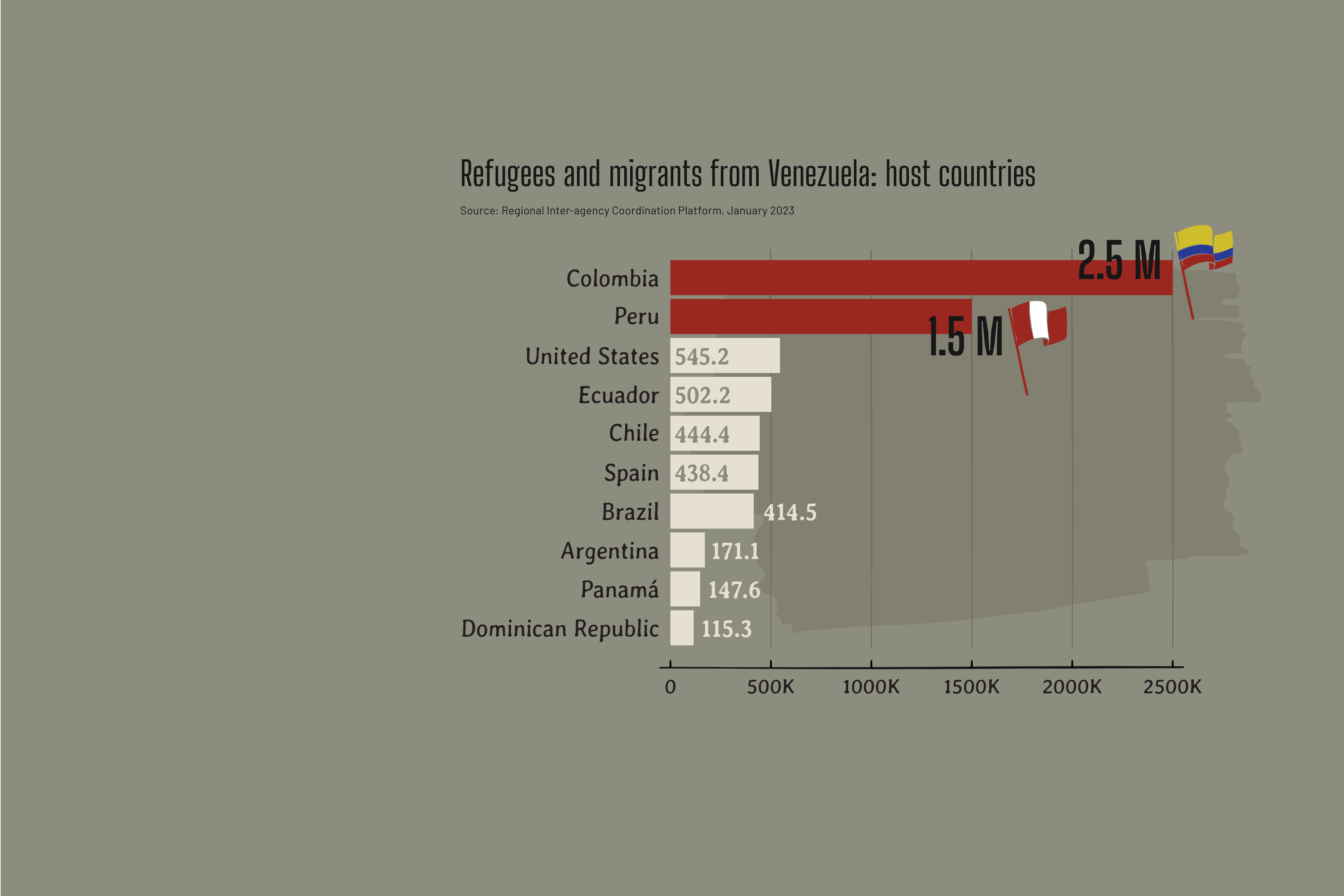

That movement coincided with rising insecurity and shortages of medicine and food that have led more than

7 million Venezuelans, about 25% of the population, to leave the country, since 2014. Colombia hosts more than any other nation.

On the Venezuelan side of the border,

Colombian guerrillas lure recruits with offers of food, jobs and goods like cell phones.

They take advantage of the poverty and hunger that are driving many Venezuelan families to despair.

With their multimillion-dollar trade in illicit drugs and illegal gold, the armed groups are changing the economy of the Venezuelan state of Amazonas.

Photo: Bram Ebus

Indigenous communities are often caught in the middle.

Alexander’s tribe, the Warekena, of whom only a few hundred remain in Venezuela and northern Brazil, is among those threatened with violent displacement as their forests are razed for illegal gold mining and armed groups expand into their ancestral territories. UNESCO has warned that the Warekena language could disappear.

Photo: Bram Ebus

A SECRET ISLAND ON THE ORINOCO

At first, the guerrilla fighters’ presence in the small Warekena community went unremarked, but they soon settled in and began giving orders, controlling who could enter and leave the area. They took charge of local justice and meted out punishments ranging from warnings to expulsion for offenses such as theft. They imposed some restrictions on fishing and patrolled the area with armed guards.

As the guerrillas grew bolder in luring Indigenous minors to their camps, a few dozen Warekena families saw only one option: escape. Alexander’s uncle, Francisco,* a 55-year-old Warekena leader, devised a plan. He organized what he said would be a community fishing trip on the Orinoco, but instead of returning home, the group settled on a small, rocky island, one of hundreds near the Colombian bank of the Orinoco River. Under blistering sun, the Warekena built their own refugee camp.

On a cloudy but sweltering morning, Francisco guided a dugout canoe along the edge of a flooded forest and beached it on a huge, worn rock outcrop that formed an island. A few steps away was his home: a shack cobbled together from plastic tarps, garbage bags and driftwood.

Seated on a log, he described how Alexander, his nephew, had slowly become trapped in guerrilla life in 2016. “First they took him on as a boat driver,” he says. “They gave his family food. They sweetened up his family. And finally, he stayed with them.”

Francisco sees no likely end to the guerrilla occupation. “They’re not going to leave,” he says. Nevertheless, he adds dubiously, “Some of the things they do are good.“ The guerrilla group pays teachers, whose government salary has plummeted, if they are paid at all. It helps with fuel to transport the sick to the hospital, and punishes thieves and violent offenders. Nevertheless, Francisco’s wife, overhearing her husband’s words as she prepares coffee over an open fire in front of the shack, disagrees.

“They’re bad,” she says, “because I know they take people’s children.”

Three young men and two young women from their community went with the guerrillas, but only Alexander, sitting next to his uncle, returned. Two years after they fled their community, the families subsist on fish and on crops they grow in small garden patches. Life on the island is not easy, but Francisco is unwilling to stand by while the guerrillas snatch the community’s young people away from their families.

“That’s why we came,” he says.

There’s one nagging worry: their sanctuary still lies in guerrilla territory. Still, he sees the island as a haven for now.

“As long as I don’t do anything wrong, I’m not afraid of anyone,” he says.

GUERRILLA CAMPS A MIRAGE OF LUXURY

To young people in rural Amazonas, guerrilla groups offer the illusion of the good life, luring them with luxuries unheard of in their communities until they are past the point of no return.

Eusebio,* a 30-year-old Indigenous man from a different community, worked for both FARC dissidents and the ELN, driving motorboats that moved troops, drugs and weapons. Like Alexander, he started living in a guerrilla camp near his village, enjoying comforts he did not have at home.

It’s like a hotel. They have the best food there. They take it easy there, watching movies.

— Eusebio, an Indigenous man that has worked for both FARC dissidents and the ELN

The relative calm and safety of Venezuela, where the rebels are not pursued by government security forces, contrasts starkly with life in Colombia, where makeshift hideouts, set up quickly under the thick forest canopy before the sun sets, are part of the daily routine.

And for those in Venezuela, the good life doesn’t necessarily last. Guerrilla combatants are rotated every two months, and some are sent to Colombia, living under strict commanders and facing frequent combat. Colombian recruits, in turn, also pass through Venezuelan camps. “They’re happy to get here,” Eusebio says. “Here you live like a king.”

Alexander was recruited by the FARC when he was still a minor. He quickly became a combatant, was sent to Colombia, and rotated among combat units in conflict areas such as Guaviare, Arauca and Cauca — the latter some 900 kilometers (nearly 560 miles) from the Venezuelan border.

And although conflict is rare on the Venezuelan side of the border, hostilities between the guerrillas and Venezuelan security forces do sometimes occur. According to Alexander, government troops from the border area who are stationed there “have relationships with the guerrillas. But those who come from [the interior of the country] don’t. They come and fight.”

The U.S. State Department has reported that Colombian guerrillas operate in Venezuela with “relative impunity” and accused the government of President Nicolás Maduro of complicity.

In 2019, concern about ELN and FARC involvement in illegal gold mining was a factor in the levying of sanctions by the U.S. Treasury Department. And in 2020, the U.S. Justice Department accused Maduro of conspiring with the FARC to “flood” the United States with cocaine.

In Amazonas, the ELN, which currently is in peace talks with the administration of Colombian President Gustavo Petro, with the Venezuelan government as a guarantor, quickly increased in size. One FARC dissident faction, the Acacio Medina front, which never signed the 2016 peace deal between the Colombian government and the FARC and therefore did not demobilize, has a longer history in the Venezuelan Amazon.

Alexander soon found that the good life was mostly a mirage. Sometimes after he had been sent to collect “taxes,” or extortion payments, from illegal gold miners, a higher-ranking guerrilla would skim some of the money, leaving Alexander to take the blame. “If someone is doing well, they won’t let him get ahead,” he says. “They keep trying to kill him until they succeed.”

FARC membership is usually for life, while the ELN allows members to leave under certain conditions. Forced recruitment is rare, however. With few options for earning money in their communities, and with food often in short supply, young people are easily tempted to go to the camps — if their fathers don’t send them first. Recruits are usually around age 15, though some are younger.

Like Alexander and Eusebio, they often start by doing odd jobs, like driving boats, which introduce them to the group. They train with a wooden imitation gun for about three months before receiving a real weapon.

In my community, you’d see little kids with wooden guns. From the smallest to the biggest, they carry their wooden guns, playing. I worked there out of need. That’s why I worked with them

— Eusebio

‘DRUG HOUSES EVERYWHERE’

Venezuela is not a significant producer of coca, the raw material in cocaine. But as neighbor to Colombia, the world’s largest coca producer, the country became a major cocaine exporter. It also is a processing center, with drug laboratories hidden under the forest canopy producing large amounts of cocaine destined for international markets.

“There were drug houses everywhere,” Eusebio says. “Those are houses where they store the drugs that go to Brazil.”

Inhabitants of Amazonas are sometimes awakened by the sound of low-flying planes. Several sources, including Colombian law enforcement agents, local residents who lived among the guerrillas, and Eusebio and Alexander themselves, say that frequent cocaine flights depart to points in South and Central American countries such as Brazil and Panama. According to Alexander, the planes are loaded and fueled in the afternoon, then take off around 4 a.m. “They go out at night.”

Eusebio moved cocaine to a clandestine airstrip two hours from his home community. “The guerrillas aren’t the ones who carry the drugs. The guerrillas stand guard, load it into the plane, watch over it. The ones who carry the drugs are the traquetos.” he says, using a slang term for drug traffickers.

Cocaine laboratories are scattered throughout the Venezuelan state of Amazonas, the two Indigenous men say. When large quantities — hundreds of kilos — of drugs have been stockpiled, shipments leave, but not always by plane. Traquetos also embark on long journeys to smuggle the drugs to Brazil by boat.

Eusebio belonged to a group of about 10 traquetos who made frequent contraband trips. When one arrived at his destination, another would depart. Revenues from the shipments were shared by the FARC dissidents and the ELN, former rivals who now have a profit-sharing pact, he says.

Presence of Organized Crime and Armed Groups

To build this database, we consulted primary sources and documents in all the Amazonian border municipalities of Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia.

On his trips down the Río Negro toward the Brazilian town of São Gabriel de Cachoeira, he would be accompanied by around eight guerrillas armed with automatic rifles and sometimes wearing uniforms and red bandanas and flying a red and black flag.

“Once I took a shipment of 530 kilos [1,168 pounds],” Eusebio says. “There was marihuana, cocaine and various types of merchandise.” Venezuelan security forces, he adds, never stopped them.

In Brazil, large crime syndicates take charge of the drugs, distributing to buyers throughout the country and exporting wholesale to Europe and Africa. But Eusebio says he never met with members of Brazilian drug gangs. Instead, he claims he handed the drugs over to rogue Brazilian law enforcement officials.

Before his boat reached São Gabriel de Cachoeira, three or four uniformed police officers would arrive, according to Eusebio. “They wait until dark to load it onto another boat,” he said.

Local media have reported on several cases of Brazilian law enforcement officials involved in drug trafficking in Amazonas. The region has seen a significant uptick in drug seizures and has become an important trafficking route since the COVID-19 pandemic.

THE LURE OF ILLEGAL ECONOMIES

Drug trafficking is not the Colombian guerrillas’ only lucrative business in Venezuela. Although mining was prohibited in Amazonas by presidential decree in 1989, illegal gold mines scar the forest in various parts of the state, including the border with Brazil and the flat-topped mountains known as tepuys, in Yapacana National Park.

During his time with the guerrillas, one of Alexander’s jobs was to collect protection money — known as a “vaccine” — from each mining claim in Yapacana National Park and an area called La Esmeralda.

“The fixed rule was one kilo of gold from each mining operation,” he says. “It has to be the full amount to hand it over to ‘El Viejo,’” the commander. If miners failed to pay, he had to take them to the commander, he says, adding, “They killed some of them.”

On the trail of illegal gold

While some gold mined illegally in Venezuela is trafficked locally to Caracas or through Brazil, gold traffickers and law enforcement documents obtained by Amazon Underworld indicate that amounts varying from tens of grams to kilograms are smuggled to Colombia by way of the Atabapo River in soap bars or deodorant canisters, or in women’s bras or intimate parts.

It may be sold in gold shops in Puerto Inírida or taken on flights from the local airport, where one Colombian gold trafficker claimed police took bribes. One smuggler reported carrying five kilos of gold by way of the Vichada River to the town of Santa Rita, then by road to Medellín.

The Colombian guerrillas have turned Amazonas into an economic powerhouse, financing operations in Colombia or elsewhere in Venezuela.

“They’re no longer working for the people, like they say they are. They’re in a war for drug-trafficking routes,” Alexander says. “Like some say, it’s not about politics anymore. They’re fighting for the drug routes, the mining and all that.”

The result is an economic opportunity that’s hard for young people to resist.

“The lack of economic resources in Indigenous and mining areas has been the perfect opportunity for persuasive maneuvering by irregular groups, selling a policy of development and security,” one Indigenous teacher and community leader says. “At the same time, the fact that they handle large amounts of foreign currency has led to the acceptance of these irregular groups in communities and in mining areas, with the government’s knowledge.”

The guerrillas are lavish with gifts to young people. “They give them things — motorcycles, even food, and this puts them into debt,” says an education expert in the state of Amazonas. “The way to pay off the debt is to join them. Before they realize it, they’re part of a criminal organization.

In San Carlos de Río Negro, a small town on the banks of the river of the same name, which borders Colombia and connects with Brazil, most students have dropped out of school. In the 2020-2021 school year, 204 children enrolled, but 50 left for unknown reasons, another 50 were recruited by “irregular groups” and 34 went to work in gold mines. The next school year, only 70 children showed up.

A senior state official in Amazonas, who also requested anonymity, admits that many students and teachers abandoned school to work in the mines or join armed groups.

“There’s government neglect and they get involved in these illegal activities,” he says, adding that the state lacks resources to visit communities that can be reached only by plane or by river, sometimes requiring weeks of travel.

On the rocky island in the Orinoco River, Alexander, the young Warekena man, who is now in his 20s, knows he got lucky. When he was caught by the Colombian Navy on the Inírida River in that country, officials did not know what to do with an undocumented foreign rebel combatant who was a minor. A lieutenant told Alexander that he was too young to go to jail, and if he declared he had surrendered voluntarily, they would let him go free.

Seated on the log, Francisco, the community leader, looks at his nephew and sighs.

“I don’t force them to stay, because they’re legally adults,” he says of the community’s oldest teenagers. He knows the move to the island did not change the conditions that drove Alexander and others like him to the guerrilla camps. The escape from their village is not a sustainable solution.

He gazes over the river, toward the Venezuelan forest on the other side.

“The door is open,” he says.

*Names have been changed

Amazon Underworld is a joint investigation of InfoAmazonia (Brazil), Armando.Info (Venezuela) and La Liga Contra el Silencio (Colombia). The work is carried out in collaboration with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network and financed by the Open Society Foundation, the U.K. Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN NL).