The poorest narcos in the trafficking chain risk even their own children to deliver drugs to criminal organizations.

10 August 2023

By Pamela Huerta, with additional reporting by Bram Ebus

Jeremías remembers the date of his river trip: It was July 20, 2021, and on the triple border shared by Peru, Brazil and Colombia on the Amazon River, a three-nation festival was under way. He was worried, because the festivities meant tighter police and military controls at checkpoints along the river. And he was just the kind of person the police would be looking for.

But he had to go. That was the day he was due to transport a shipment of cocaine base paste, a cocaine precursor, that he had produced at his farm. Buyers were waiting in the Brazilian border town of Tabatinga, and he couldn’t fail to show up.

Then he had an idea. If he traveled with his 9-year-old daughter, he’d be less likely to raise suspicions. What could be more ordinary than a father taking his daughter to the festival? And she was always ready for adventure.

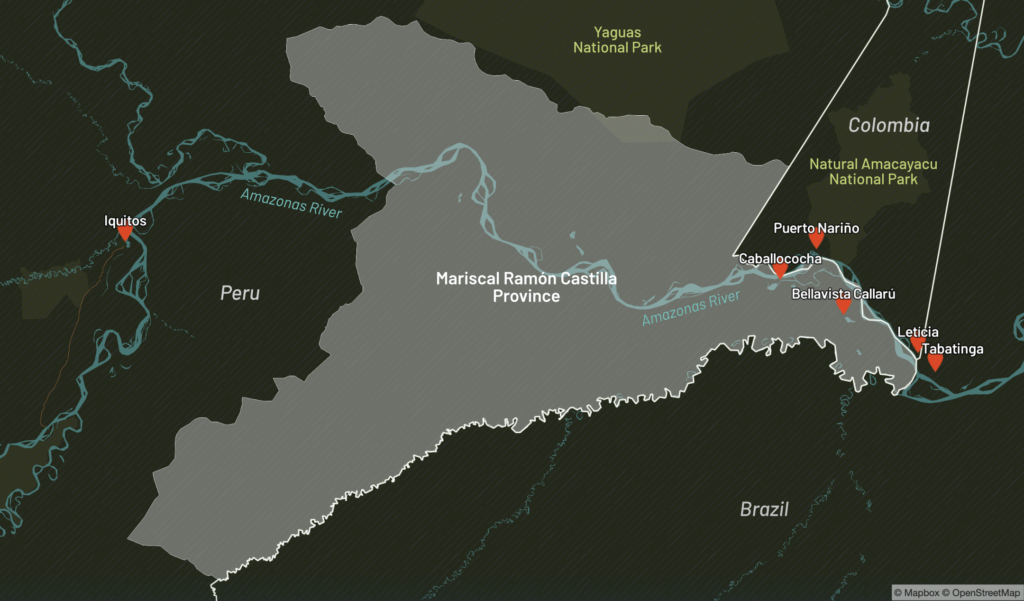

“She said, ‘Come on, let’s go!’ She wanted to take the risk. Either you get caught or you get through to your destination. That was the concern about taking her along. But you have to stay calm. She already knows that,” he recalls, sitting on a rough wooden bench outside his house in one of many Indigenous communities in Mariscal Ramón Castilla, a province in the far northeast corner of Peru that borders Colombia and Brazil.

He adds matter-of-factly, “Here in town, DIRANDRO [Peru’s anti-narcotics police] has almost caught us twice.”

The gambit paid off, though, and his luck held. It was the first time he’d involved his youngest daughter in his drug-trafficking travel.

But after that she became his partner, providing cover for some of his border trips.

Video: Pamela Huerta

As an extra precaution, she would hide the drug money under her clothes on the way home.

If police got suspicious and searched him, they’d find nothing.

Video: Pamela Huerta

Jeremías* believes she’ll take over the business eventually. It’s an ideology, he says. Just as he followed in his father’s footsteps, she will follow in his.

His father transported cocaine base paste. Jeremías manufactures it, and his daughter helps him by deflecting suspicion and concealing money.

“Once, when we were returning home after delivering packages, I had to bring more than 100,000 reais in cash,” he recalls, referring to Brazil’s currency.

“Almost all of it was to pay the coca pickers and buy supplies for the next season. She helped me with that, too — she brought it, attached to her body. Who’s going to say anything?” He smiles, though whether that’s from nerves or cynicism is hard to tell.

Jeremías and others like him in Mariscal Ramón Castilla are the first links in a chain of drug production that stretches from fields of coca, the plant whose leaves provide the active ingredient in cocaine, through clandestine laboratories nearby, down the Amazon River to the triple border, then by river or air to cities on Brazil’s Atlantic coast and on to consumers in Europe.

Known as a patrón, a local drug-trafficking boss, Jeremías has his own coca crops and oversees fields on other people’s farms. He coordinates the processing of coca leaves into cocaine base paste, which will later be refined into cocaine hydrochloride. He and the people around him — the ones who spend the day picking coca leaves in the tropical heat, and those who mix the leaves with toxic chemicals to produce the paste — are also among the lowest-paid workers in the illegal drug industry.

Besides growing coca and manufacturing base paste, he used to transport his wares to the triple border. Then outsourcing came to the drug trade in this part of the Amazon. Now middlemen from Colombia have taken over the logistics, picking up the drugs from the farm and saving him the long and possibly perilous journey to Tabatinga.

Thirty-odd years old, Jeremías is a family man with a military bearing who rarely uses the familiar form of addressing people in Spanish. He is not a man of few words, but his deliberate way of speaking gives a listener that sense. If he could have chosen, he says, he would have been a soldier, because he likes guns.

COCA EXPANSION OUTSTRIPS ERADICATION

Mariscal Ramón Castilla has long been a land of original peoples, where the Indigenous Ticuna, Yagua and Bora peoples still predominate. Until the 1990s, it was just a transit point for drugs heading for the triple border. The source of the coveted white powder was far to the west, on the slopes of the Andes Mountains, far from this seasonally flooded, low-lying plain. The Amazonian lowlands were not suitable for agriculture, but they had enormous strategic potential because of their location.

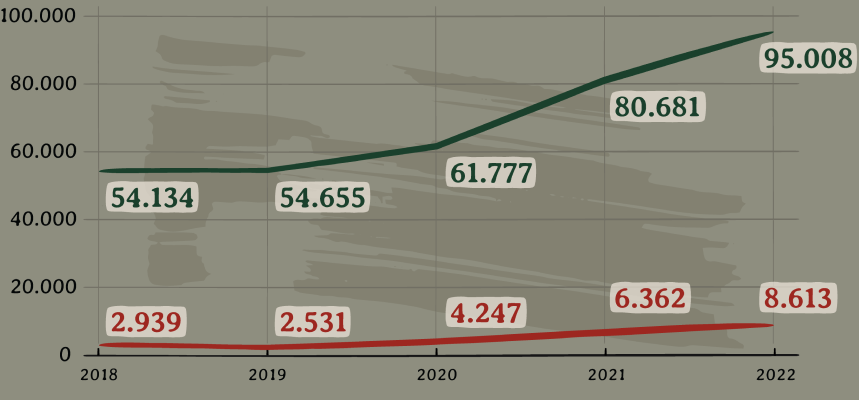

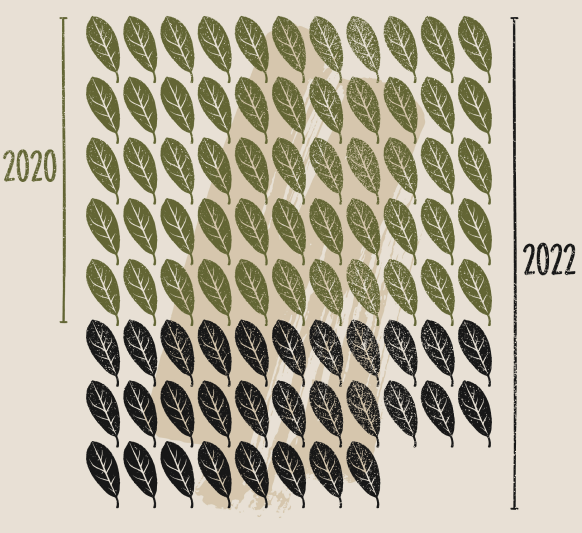

More than 20 years later, 8,613 hectares (33 square miles) of forest have been replaced by coca crops, acoording to the National Commission for Development and Life without Drugs (DEVIDA), Peru’s anti-drug agency.

Area planted in coca: Province of Mariscal Ramon Castilla & Peru

Province of Mariscal Ramón Castilla

Peru

Although Colombia is the largest coca producer, Peru has more coca crops in the Amazon basin than any other country, according to a 2023 report by the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). And Peru is second only to Colombia in cocaine production.

According to Carlos Figueroa Henostroza, executive president of DEVIDA, estimated production in 2022 was

870 TONS, 304 MORE THAN IN 2020,

when the last report on potential cocaine production was issued.

Those figures contrast sharply with the area of coca uprooted by the Special Project for Control and Reduction of Illegal Crops in the Upper Huallaga (CORAH, for its Spanish initials), the agency responsible for eradicating coca crops in Peru. According to official figures, the last time operations were conducted to eradicate illicit crops in Mariscal Ramón Castilla was in 2019, when 7,784 hectares (30 square miles) of plants were uprooted. That effort focused on Pebas, a district in Mariscal Ramón Castilla upriver from the triple border, which can only be reached by river.

So far this year, government officials report nearly 5,000 hectares (19.3 square miles) of illicit crops eradicated, but only in the regions of Ucayali, Huánaco and San Martín. In December 2022, CORAH set up a base of operations in Mariscal Ramón Castilla, raising both expectations and fear in local residents. As of June, however, the base was unoccupied. The Interior Ministry did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Julio César Vela Utor, a retired National Police general who is executive director of CORAH, says eradication depends on a multi-agency strategy that focuses efforts mainly in areas where the eradication team’s safety is assured and there are possibilities of alternative development for local residents.

Added to that, however, are budget limitations that make it impossible to meet annual eradication targets.

To meet CORAH’s annual eradication target of 25,000 hectares (96.5 square miles) and inspect all the remote and difficult border areas, the agency would need between US$47 million and US$50 million a year, Vela Utor says. In the past three years, however, the agency’s annual budget has been barely half that amount.

THE POOREST LINKS IN THE DRUG CHAIN

Jeremías has more than a dozen hectares (about half a square mile) of coca crops of his own in Mariscal Ramón Castilla, rents a few more, oversees the harvest in fields belonging to “friends” and buys some coca leaves from other farmers. All goes to producing base paste in his laboratory. That degree of control over production makes him a trafficking boss, although it seems an ostentatious title for a man who has only managed to build his house little by little, over four years.

In the drug production chain, the patrón is the person who provides base paste or cocaine to middlemen at a fraction of the price the drug will eventually fetch on the streets of a city in the United States or Europe. Local bosses like Jeremías are at the mercy of the market, and in the economic underworld, that market is not self-regulating. That makes the Peruvian patrones and their hired hands the poorest links in the drug-trafficking chain.

Prices are set by buyers, who on the triple border usually belong to the criminal organization that dominates the trade in Tabatinga. Since 2020, according to the Peruvian anti-drug police, a group known as “The Kids” — Os Crias in Portuguese, or Las Crías in Spanish — have been in control there.

The rise of Os Crias was the outcome of a bloody dispute for territorial control of the triple border among the Comando Vermelho (CV), Familia do Norte (FdN) and Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), three of Brazil’s main criminal organizations. Unwilling to share the drug trade in that area, they weakened each other in an ongoing struggle for dominance. Dissidents from the three groups came together, setting aside their old loyalties and forming a criminal consortium catering to the highest bidder. For the moment, at least, they have cornered the market on the drugs that arrive from collection points in the province of Mariscal Ramón Castilla.

Presence of organized crime and armed groups

To build this database, we consulted primary sources and documents in all the Amazonian border municipalities of Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia.

One of those points is Caballococha, the largest town in Mariscal Ramón Castilla, which boasts a few streets of shops and an unfinished port dominated by a statue of a rearing white horse. Sitting in the plaza on a Sunday morning, Jeremías is impatient to begin the next harvest. He plans to return in the afternoon to the community where he lives with his family, and where he has operated his business for the past 14 years. It’s a four-hour trip by boat, and he must leave soon to arrive before nightfall.

In recent months, Jeremías has diversified his business, and not by chance. Besides the soft drinks and beer that he has been selling, he also sells gasoline, which is used not only to power boats but also to extract the cocaine alkaloid from the coca leaf to make the cocaine base that is later refined into cocaine.

Jeremías also has a new foreman, a good-natured, 51-year-old Colombian who says he left his country because the government there wouldn’t let him grow coca in peace. During the harvest, he will work side by side with a squad of raspachines, or leaf pickers, who will be paid the equivalent of between $0.21 and $0.27 per kilo (2.2 pounds) of coca harvested. Working up to 15 hours in a day, a harvester can pick as much as 150 kilos (330 pounds). Many have hands so callused that they no longer feel pain from the work.

Carmelo*, an 18-year-old Colombian, began harvesting coca when he was 16. He didn’t finish elementary school and expresses no expectations about his future. He doesn’t know what he would have liked to have been or done, let alone that he still has time to decide. What he does know is how much the blisters on his fingers hurt after picking so many sacks of coca leaves, and what it feels like to fall ill from exhaustion or an insect bite.

He also knows that he might have ended up in jail at least once, but he managed to slip away from the anti-drug police. “They made us run — they attacked the laboratories. I escaped. They beat us up and sent us to Iquitos.,” he recounts anecdotally.

The path to Jeremías’ field is muddy, with scattered vegetation because the forest has been cleared to expand the illicit crops. Without tree cover, the temperature is hellish. Jeremías sports a synthetic soccer jersey with the logo of the Argentinian team Boca Juniors and the number 17, worn by Peruvian player Luis Advíncula. Like most Amazonian farmers, he always has a machete in his hand.

Along the way, he points out the laboratory where he processes the leaves and laments that this year he can’t hire a chemist to take charge of making the base paste. He doesn’t mean a professional chemist, necessarily, but one who has learned the trade from experience. This year, he says, he can’t afford to pay one because the increase in fertilizer prices has blown his budget.

DON’T ASK, DON’T TELL

Jeremías knows the drug he produces will end up in Brazil. Until six months ago, he transported it himself, along with his youngest daughter. Now, though, buyers arrive to pick it up at his house. Most of them are Colombians, but they may be financed by Peruvians or Brazilians. As long as he gets paid in cash, he doesn’t ask questions. “Once I sold to a Mexican, but he never came back. I think they killed him,” he says matter-of-factly.

Besides Tabatinga in Brazil, there are other important points where buyers stockpile drugs, including the Colombian towns of Leticia, which adjoins Tabatinga on the triple border, and Puerto Nariño, slightly downstream from Caballococha and on the other side of the Amazon River. In Peru, there is Santa Rosa, on an island opposite Tabatinga and Leticia, and the Indigenous community of Bellavista Callarú, about midway between Caballococha and the border.

Drug route follows the Amazon River

Traffickers stockpile drugs at several points along the Colombia-Peru border, on the transportation route to Tabatinga, Brazil.

Bellavista is increasingly controlled by drug-trafficking groups. It is a community on the bank of the Callarú River, which is only navigable in the rainy season, and where soccer is a favorite activity of both men and women. Its plaza — an overgrown area with some stairs and arches — offers a view of spectacular Amazonian sunsets, a beauty that contrasts with the sight of armed outsiders drinking beer until they pass out.

Strangers who are allowed to enter are followed and harassed with questions meant to intimidate. On March 21, a young victim of sexual exploitation was murdered and no one ever spoke up, one local resident says. People know who killed her, but no one will say anything, the person added, because “that’s what happens when you don’t play straight with a patrón.”

Coca is the only law. On June 15, a familiar announcement was broadcast over the community’s loudspeakers in Spanish and Ticuna, the local Indigenous language: “This is a notice to anyone who wants to go pick coca in Lucho’s field.”

Scenes like that are not unusual. Neither is the exploitation of minors, according to one curaca, or leader, of an Indigenous community on the Colombian side of the river, who says armed men have gone to her house at night and threatened her because of her efforts to discourage community members from letting young people go to work in the coca fields in Peru.

Men are taken to the fields and women to the bars, the leader says. “Don’t let the girls go — they take them, have sex with them and raffle them off,” she warns parents who have daughters over age 11. The curaca also worries about the increasing problem of drug use among young people, who, lured to pick coca by offers of money, often are paid in cocaine base, which they then sell in the community.

Delivering drugs on time to buyers in Tabatinga and Leticia, down the Amazon River on the triple border, is also a specialty.

Video: Pamela Huerta

Boat drivers, known locally as merqueros, are the logistical link in the drug-trafficking chain and have one of the riskiest jobs.

They don’t get rich running drugs, but that line of work gives them a certain economic stability.

Video> Pamela Huerta

The knowledge that drug traffickers in Colombia have acquired over the years is sought-after in Peru, says Col. Carlos Urquijo Gómez, second commander of Colombia’s Jungle Brigade No. 26 in Leticia.

Mario* is from Meta, Colombia, an area of constant conflict between guerrillas and paramilitaries. If you get involved in this work, he says, it’s because you want easy money. He gave it up for that reason, and also out of fear, because he found out how they’d killed his best friend. Before the pandemic, he shuttled drugs from Puerto Nariño to Tabatinga, the first stage of a route that leads to the Atlantic coast and then to foreign markets. He smuggled base paste and always carried a revolver.

“I transported drugs hidden in cassava or bananas, or sometimes in jerry cans of fuel,” Mario says, eyeing an armed soldier who enters the shop where he is talking with a visitor. He carried small amounts, between 10 and 20 kilos (22 to 44 pounds), which could be worth around US$200 to him once he’d deducted travel costs. He was always afraid, especially of Brazil’s Federal Police. Nevertheless, he says, “The trade there moves freely.”

In Tabatinga, a kilo of cocaine base paste can cost as much as US$1,000 and a kilo of cocaine between US$2,500 and US$3,000. It all depends on the quality of the product, security conditions and a series of factors based on the “here and now.” From Tabatinga, the drugs go to Manaus, Brazil, the largest city in the Amazon and the main stockpiling point for that country’s criminal organizations, which handle domestic distribution and shipment to coastal ports.

These dynamics make the area around the triple border extremely violent, with an exponential increase in murder for hire, human trafficking and general criminal activity. Colombian police statistics show a sharp increase in murders in Leticia, from seven in 2020 to 33 in 2022, making it the municipality with the second-highest homicide rate in Colombia.

The 2023 World Drug Report by the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) continues to show Brazil as the largest consumer of drugs in South America. The country’s Atlantic ports are also a gateway for exporting cocaine to Europe, eastern Asia and the southern part of Africa. In those markets, a kilo of cocaine can cost as much as US$80,000.

STREAMLINING THE BUSINESS

Jeremías, his foreman and Mario are small but important gears that keep the drug-trafficking machinery running smoothly. The same is true of the farmers who grow the crop, the workers who trample the leaves with toxic chemicals to make base paste, the cooks who prepare meals for the coca harvesters, the “backpackers” who carry heavy loads of drugs on foot across borders, and the other players in this perverse and illegal business. In this part of Peru, the outsourcing of services makes it difficult to figure out who’s in charge. The family clans, kingpins and drug cartels that once controlled the entire chain have become obsolete.

Diego Quintero Martínez, UNODC coordinator for security and emerging crimes, says the illicit drug trade has adopted a business model that makes the crime of drug trafficking increasingly difficult to tackle.

At first there was a very linear structure, where the person who was the head of the cartel controlled the entire process. But nowadays we see that there are subsystems.

Diego Quintero Martínez, UNODC coordinator for security and emerging crimes

This is reflected in recent events. When the Familia do Norte lost control in Tabatinga, Os Crias — literally its “kids” — emerged. When Mexican drug boss Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán was captured, the “Chapitos,” his successors, appeared. The word “indispensable” no longer has any meaning in the drug underworld.

The drug trade has a long history of adapting to — or staying a step ahead of — socioeconomic changes. It innovates. That may be one reason why efforts to eradicate it are largely unsuccessful. In the province of Mariscal Ramón Castilla, DEVIDA, Peru’s anti-drug agency, has been working on alternative development projects since 2014. So far, however, efforts to get farmers to switch from coca to other crops have not borne fruit.

Jeremías thinks those efforts are useless, because crops like cacao, from which chocolate is made, aren’t profitable.

“They try,” he says, “but there’s no market, and transportation costs make everything expensive.”

Jeremías knows that his work supports a multibillion-dollar trade of which he gets only crumbs. If he could earn the same amount or more doing other work in Peru’s Amazonian lowlands, he says, he’d give up the illicit drug trade.

“But the way Peru’s borders are, they’ve abandoned us,” he says of the government. “Forget it!”

He’s thinking about going into politics in his district in the future. He says he’d like to help his people, but it’s also the only option in Mariscal Ramón Castilla that could equal or exceed his income as a patrón. For the time being, though, he doesn’t see much of a choice — he’ll continue being a relatively poor drug drug boss, like so many others in the first link of the trafficking chain.

* Names have been changed.

Amazon Underworld is a joint investigation of InfoAmazonia (Brazil), Armando.Info (Venezuela) and La Liga Contra el Silencio (Colombia). The work is carried out in collaboration with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network and financed by the Open Society Foundation, the U.K. Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN NL).